A writer asks if there is order in chaos.

On LuLu Miller's "Why Fish Don't Exist" and Darwin, too.

Miller’s narration of this adventurous and complex book only adds to the brutal sincerity of her voice. I can only aspire to write with her honesty. In the book, she sets out to discover why the scientist, David Starr Jordan, (later the president of Stanford) pursues a lifelong compulsion to find order somewhere in the universe.

In 2014, Mary Healy, the Director of the Sacramento Zoo, led a tour to the Galapagos. It was not something I could either afford or pass on–for two reasons. Seas were rising, and “life is short.” Mary was to prove that life really is short. I dedicated an essay to her then, and I’m doing that again now.

In Miller’s deep dive into Jordan and his obsession with order and genetics, she asks if order can be found in chaos. I will mention that towards the end of the book, she finds that Jordan held some very disturbing views about genetics, and he wasn’t the only one. My point here is that Miller has inspired me to revisit my trip to the Galapagos. Did I see order there? No. I saw a frenzy of diversity and adaptation, which is what makes species strong.

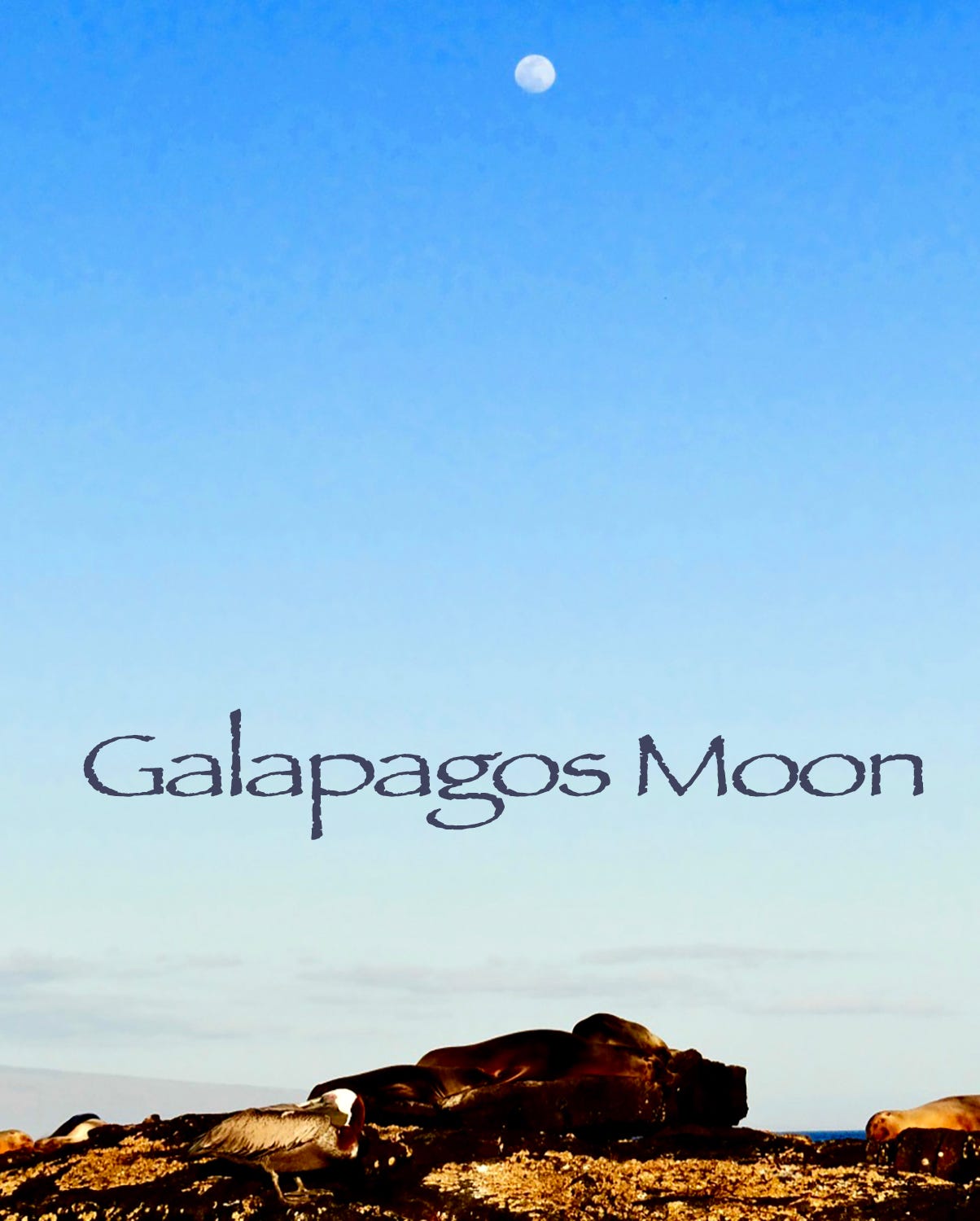

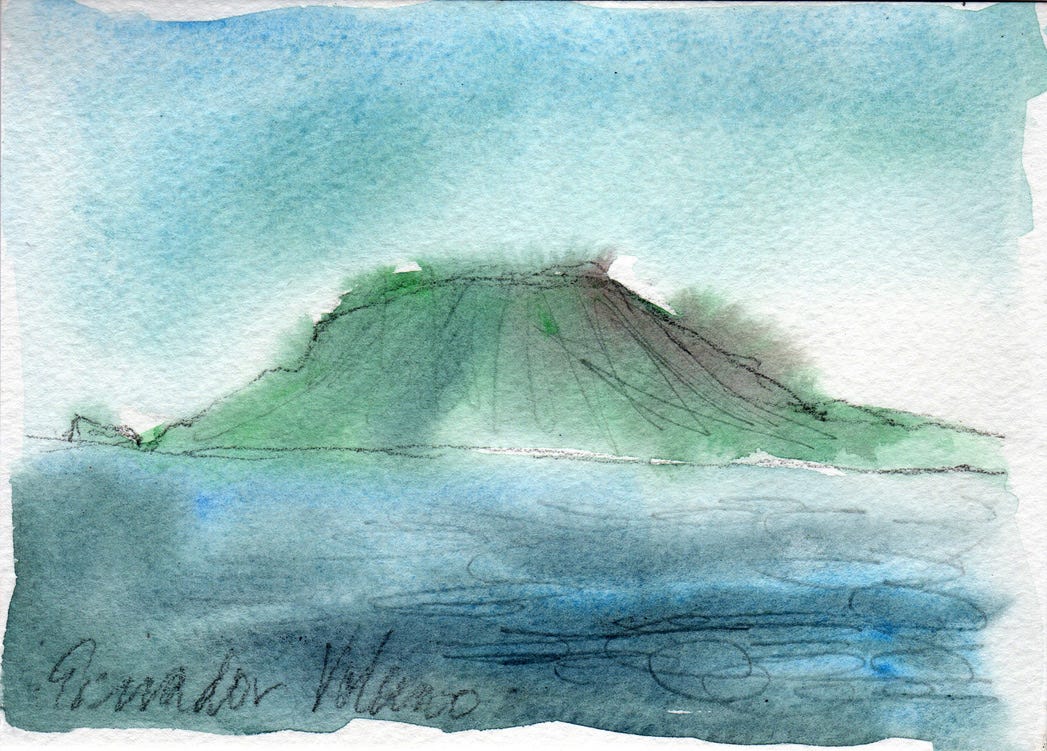

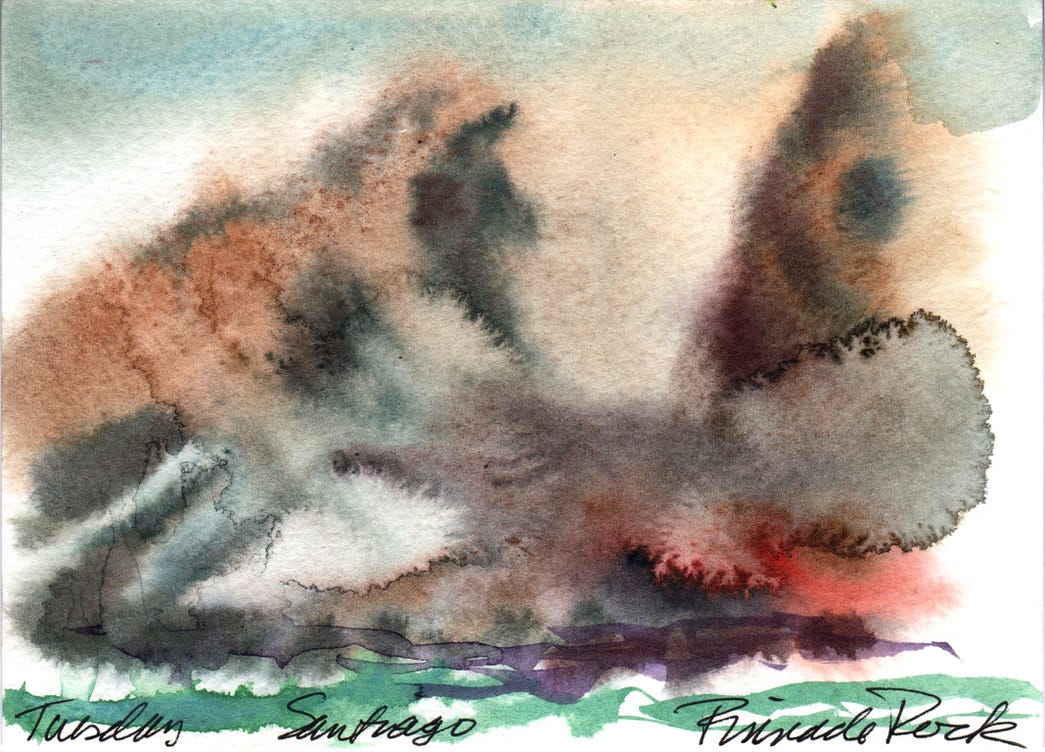

The Galapagos, August 2014

A moon appeared one day, impossibly plump and stark against vivid skies. All creatures reveled, sunned themselves, cavorted, slid in and out of warm waters. Several humans joined them in the sea, flippered and masked to explore what couldn’t be seen from bobbing zodiacs, engines stilled. Currents were swift, and divers, tempted to follow a tortoise, seal, or iguana, had to be cautious. Heat lingered above the water, as if tempted to kiss, but too shy.

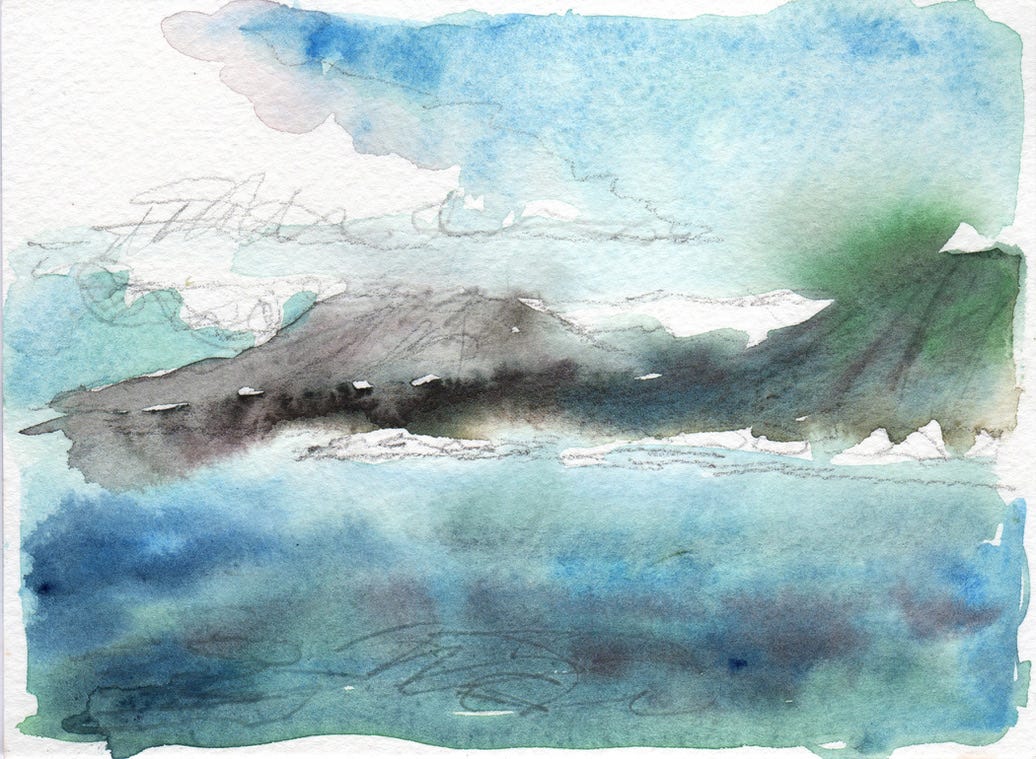

Tropical sun disappeared into the sea as adventurers settled in after cocktails and a lavish dinner. The crew readied the sixteen-passenger catamaran for a night crossing from one ancient volcanic island to another.

Waves slapped the sides of the vessel, a gentle and reassuring sound in concert with engines. I sank exhausted and happy into the only chair on the cabin’s tiny deck.

We’d crossed the Equator, my first time, and in fact my first in open seas. Should have been intimidating, so deep, so unknown. I both thrilled at and resented the moon, which like urban light pollution, had rendered the stars invisible. It dominated each and every star in the heavens, ravishing each wave with light, as if in defiance of the black sea below.

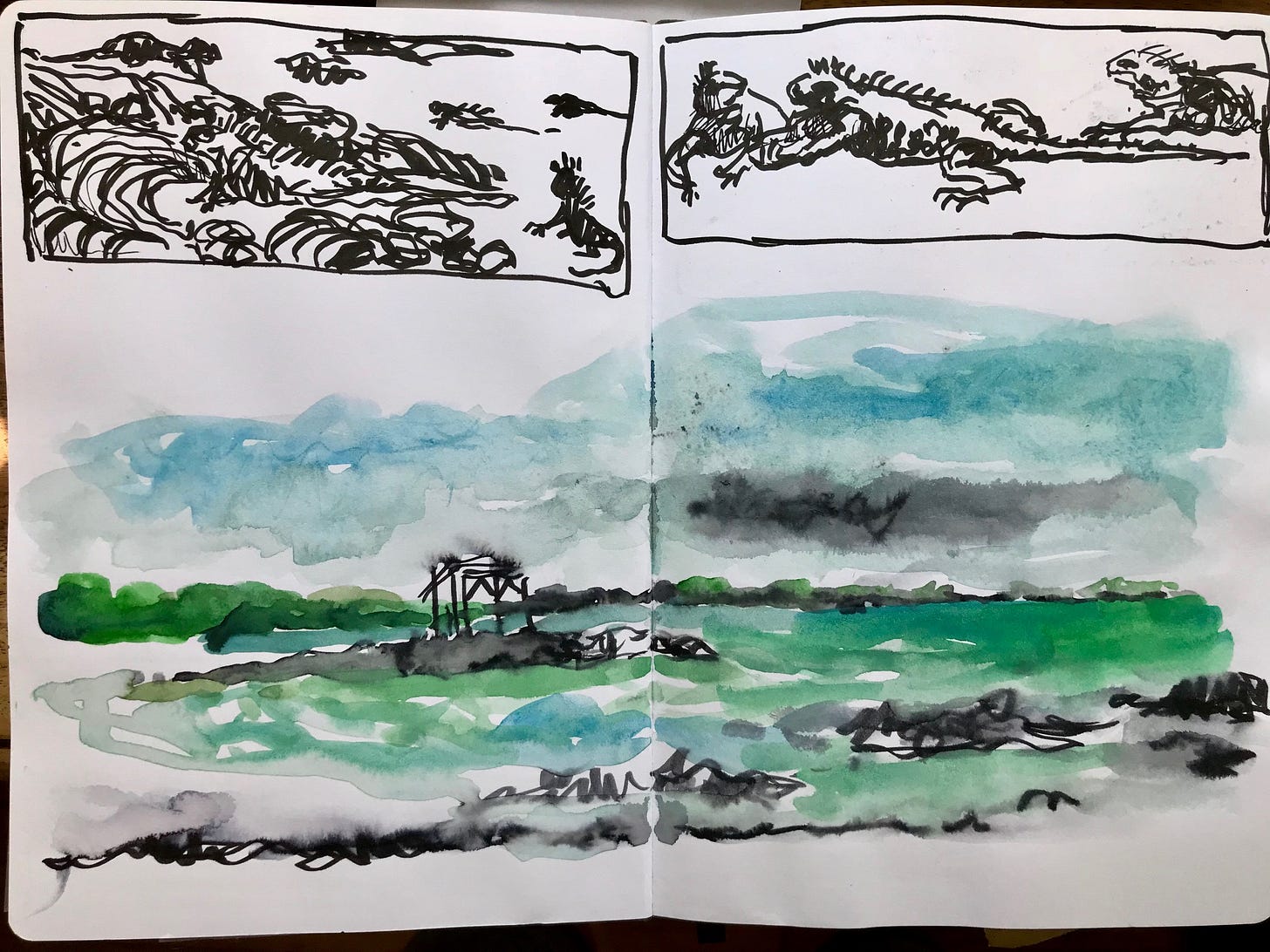

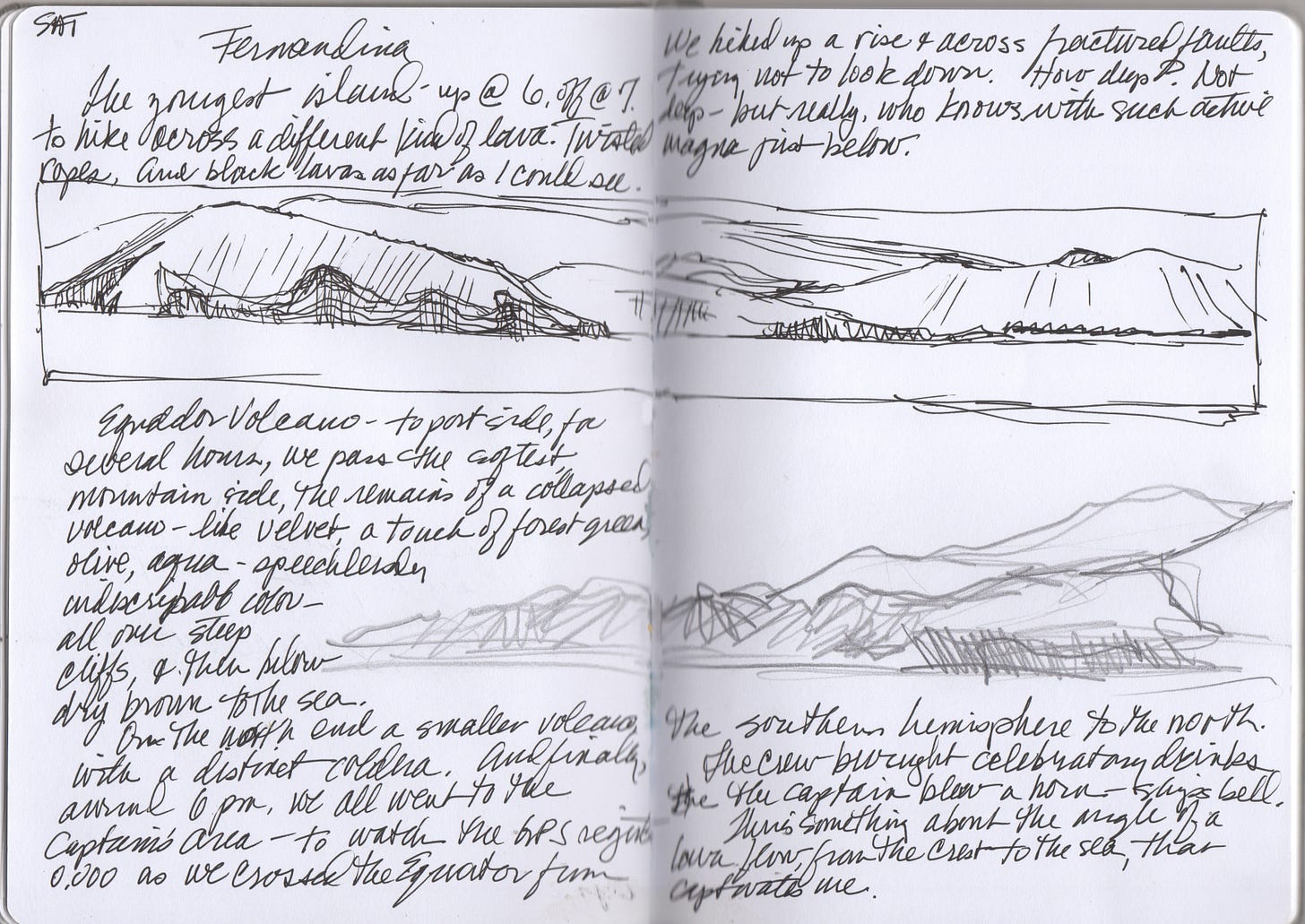

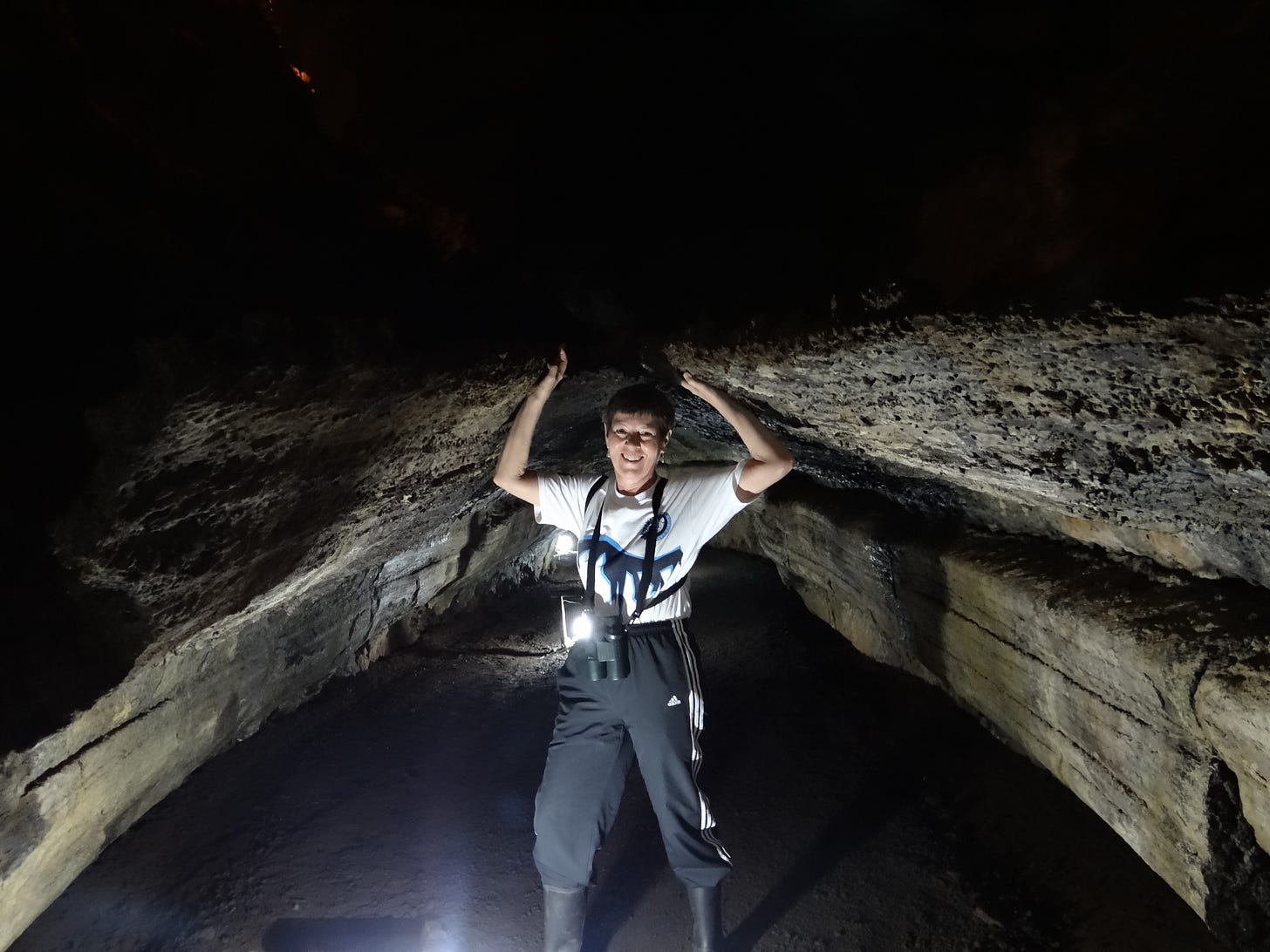

When I look at all my sketchbooks, I remember walking over lava flows tortured by heat, searing in tropical sun. Black and colorful iguanas, Darwin’s finches, bright red and blue crabs, Blue-footed Boobies, Flightless Cormorants, and an encounter with a Killer Whale.

Here are Darwin’s fearless creatures. Blue-footed boobies and frigates with babies dot a plateau teeming with life, in the air, in trees, on the ground. Birds perch on rocks profuse with dripping guano, lending an air of surrealism to a landscape of stark contrasts.

It’s mating season. With the remarkable diversity that has made these Pacific islands famous, each species exhibits distinctive traits and rituals. Booby males dance, raising one cerulean webbed foot at a time, tilting to the other while emitting a long melodic whistle and spreading wings wide. Frigate males, their blazing red throats transformed into balloons of impossible size, wait with great expectation.

In 1835, Darwin explored five islands in five weeks. I visited eight islands in eight days. His group wandered a living laboratory. Mine was tightly controlled to protect a fragile ecosystem. He said “it seems to be a little world within itself.” From his descriptions of the two islands we both explored, it appears little has changed. Creatures like Darwin’s finches die or adapt to endless challenges. The islands evolve, a microcosm of survival stress.

Of course, like everyone, I took about a thousand pictures. But it was the drawing that stopped time. How an island would look like some creature coming out of the sea, and then coming closer, details are revealed.

I’d go back in a heartbeat (if someone would pay my way). I hear that now the Islands aren’t as controlled, the boats are overrunning the place and problems are accelerating. Seems like the only thing we can count on is chaos. Except for one brief second when this particular Galapagos Hawk and I shared a moment.

Mary Healy, 1952-2014, passed away on our ship at the end of the first day in the Islands. As mentioned, she was a friend who confirmed something we all need to remember. All my appreciation to all of you. Please share and comment.

Wow, thanks for that story. Sad poignant hook at the end. In our world of a billion digital images a day, w/c remains timeless.