I poached the phrase “encroaching desolation” from an article about Las Vegas. It’s not a place I’ve ever wanted to explore and did so infrequently. From my visits, I saw that desolation is contained within the city itself, from broad and brightly lit avenues to lurid signs, fake architecture, and walkways littered with souls for sale.

It wasn’t until I was contracted to create murals for Bally’s Casino on the Strip that I spent any time there at all.

In the early 90s, Vegas was trying to rebrand itself from a 70s sleazy gangster town to a family entertainment destination. A new player had opened on the Strip in 1989, and the older, wearier properties were forced to respond. The Mirage, the largest hotel in the world, is reputed to have been the first resort financed with Wall Street junk bonds. It revolutionized Las Vegas and the Strip with an elaborately expensive theme, exquisite detail, and an immense fish tank behind the front desk, 52-feet long and 8-feet tall, containing a thousand specimens.

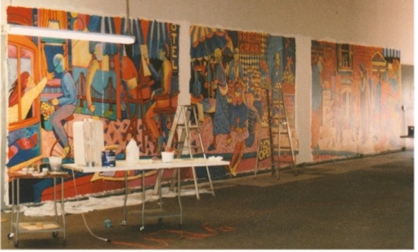

I’d been working on various projects with a big design firm in Los Angeles. They commissioned me to create 1,000 square feet of murals for Bally’s, for a large café just off the main casino. I proposed the more materialistic side of Los Angeles as a theme, with larger-than-life humans shopping and recreating. The colors were garish, with people more caricature than realistic. The client had a deadline, with carpet ordered, huge expenses, and nervous architects. This wasn’t the kind of project that didn’t get done on time and on budget. The notorious desert surrounding Vegas was full of people who hadn’t performed as promised.

My studio was a 4,000 square foot concrete box in a small industrial complex two miles from my house. It was hot in summer, cold in winter, and so large that I rolled around on skates. In order to stretch 200 feet of canvas on my studio wall, I had to move electrical conduit and boxes that ran down the middle of the wall, 3 feet from the floor. My spouse, a general contractor, spent the morning moving electrical, and left in mid-afternoon to pick up kids and check in with his mother, who’d recently moved in with us.

Within an hour my husband returned. Surprised, I asked, “What are you doing back here?” Years later I’d look back at this moment as the tipping in my marriage. From that moment, it was one of survival rather than partnership.

As we worked in my studio, his mother, one of my best friends, had left our house for a luncheon. As she waited for a light to turn, a very old person had driven down the wrong side of a major street for a mile, accelerated through a parking lot, hit a concrete tire barrier and at the point of impact, became airborne. I can only hope that our mother died instantly, that she didn’t look up momentarily to see a grill just feet from her face.

I had no time to grieve. Bally’s had a deadline. I asked one of my assistants to bring a bottle of tequila, and every once in a while, as panic and despair hit, I’d grab a nip and get back to work. Maybe it was then that I learned that my work was to be my salvation, my escape.

When the painting was done, I rolled up the canvas, got on a plane, and flew to Vegas. Installers were waiting for me, and as they hung each panel, I followed behind for touchups.

Walking through the casino with the project architect, I pointed to 250 feet of deadly dull mauve wall at reception, and said, “You need to do something about that.” He said, “Bally’s is in bankruptcy and can’t afford it,” and I replied, “With the Mirage down the street, you can’t afford not to do something.”

Two months later I got the project: another 1000 square feet of murals. I proposed an intimate view of Bally’s, something quite unique for Vegas. Not slick, not perfect. A human back-of-the-house view. That the concept was approved is remarkable, and the murals stayed up for over 8 years, a record for that kind of establishment. Dealers, cleaners, waiters, and entertainers. Portraits of the Everly Brothers, Dean Martin, Rodney Dangerfield, and my favorite, the review dancers. Most surprising was that the dancers, topless on stage, were quite modest in their dressing room. I portrayed them as professionals, doing hair and makeup, putting on costumes.

For each trip, I was only in Vegas long enough to feel a shallow and soulless quality. It wasn’t a place I wanted to be, no matter how much they were willing to pay.

By the time I returned in 2015 for a water conference, original art in casinos had been replaced with digital reproductions. Bally’s was musky, dirty, neglected. Hustlers stood on the Strip handing out cards for hookers. The California drought had begun, as the Mirage’s famous fountains projected water high into hot summer air in a dramatic display, evaporating. Desolation was encroaching.