Introduction

The subject of education is dominating current news. This is an essay that I wrote on February 23, 2018 about my dear friend, the late Carl Bradley. On April 21, 2018, my essay about Carl and his experiences at Little Rock was published in the Sacramento Bee. You can’t read it unless you pay, so I’m posting an earlier version here; it’s essentially the same.

About Carl Bradley

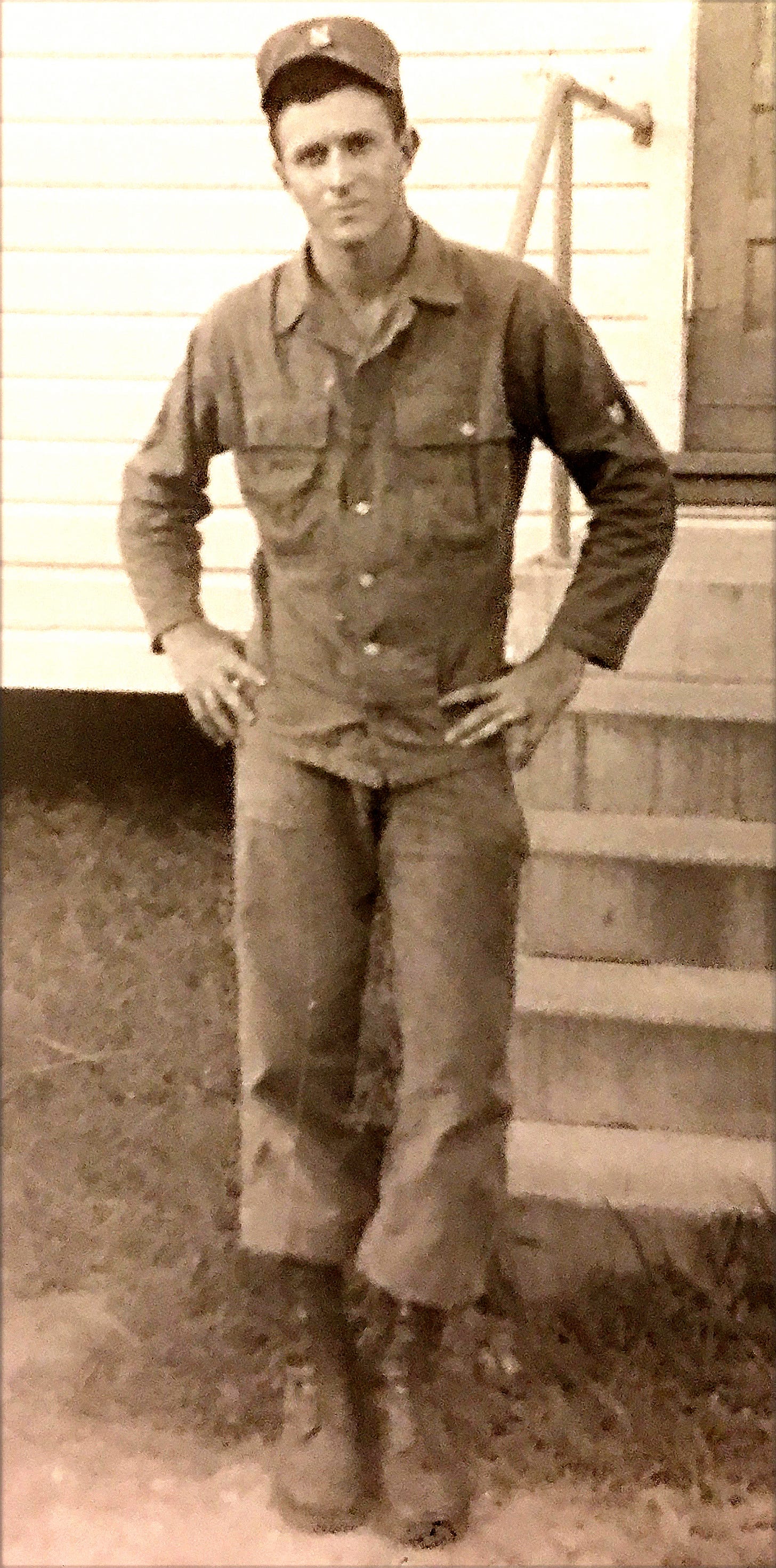

Carl Bradley is white. He’s so strong and healthy that you’d hardly call him old, despite his 78 years (in 2018). He’s a modest fellow with a gentle face that belies his history. He looks sad because he’s here for the funeral of his partner, my best friend.

Carl’s a railroad man. He worked his way up from age 20 in 1960, to management: from Arkansas to California. The railroad was segregated then. He began as a brakeman for the Union Pacific. Black workers got the hardest labor like driving spikes, he said, until policy changed in 1975. He was promoted to management in 1976 and was transferred to Roseville in 1997. I met him in 1999 while creating a mural for the California State Railroad Museum.

He came to California as the General Superintendent, managing the $145 million rebuilding of American history’s iconic railyard in Roseville, the western terminus of the Transcontinental Railroad. He managed design, construction and operations, transformed outdated infrastructure into the largest railyard in the US. He managed 3,500 people, from architects to brakemen, from Bakersfield to Klamath Falls.

This is the story he told me about Little Rock and how it defined his career.

Carl witnessed history

At sixteen, he lied about his age to join the National Guard, in Pine Bluff, south of Little Rock. He’d been working since he was 10, to help his family of eight. In a completely segregated town, he didn’t have black friends. It was the kind of town where white kids threw rocks at black kids; he says he didn’t.

On September 3, 1957, at 9 at night, his mother answered the phone. Carl was ordered to report to active duty by 11pm. High schoolers who’d never received basic training left Pine Bluff in a convoy driving north about 45 miles, and pulled into a football stadium.

Central High School, the first day of integration

It was the first day of school. The governor of Arkansas had ordered 100 National Guardsmen to surround and protect white children from children who wanted equal opportunity and access to an education. Black children.

At a nearby base, Carl received riot training – with 3’ long clubs. “No rifles, just taught to disable and/or hurt people.” He was teargassed – to learn not to panic.

The nine black students arrived every day, and every day they were kept out.

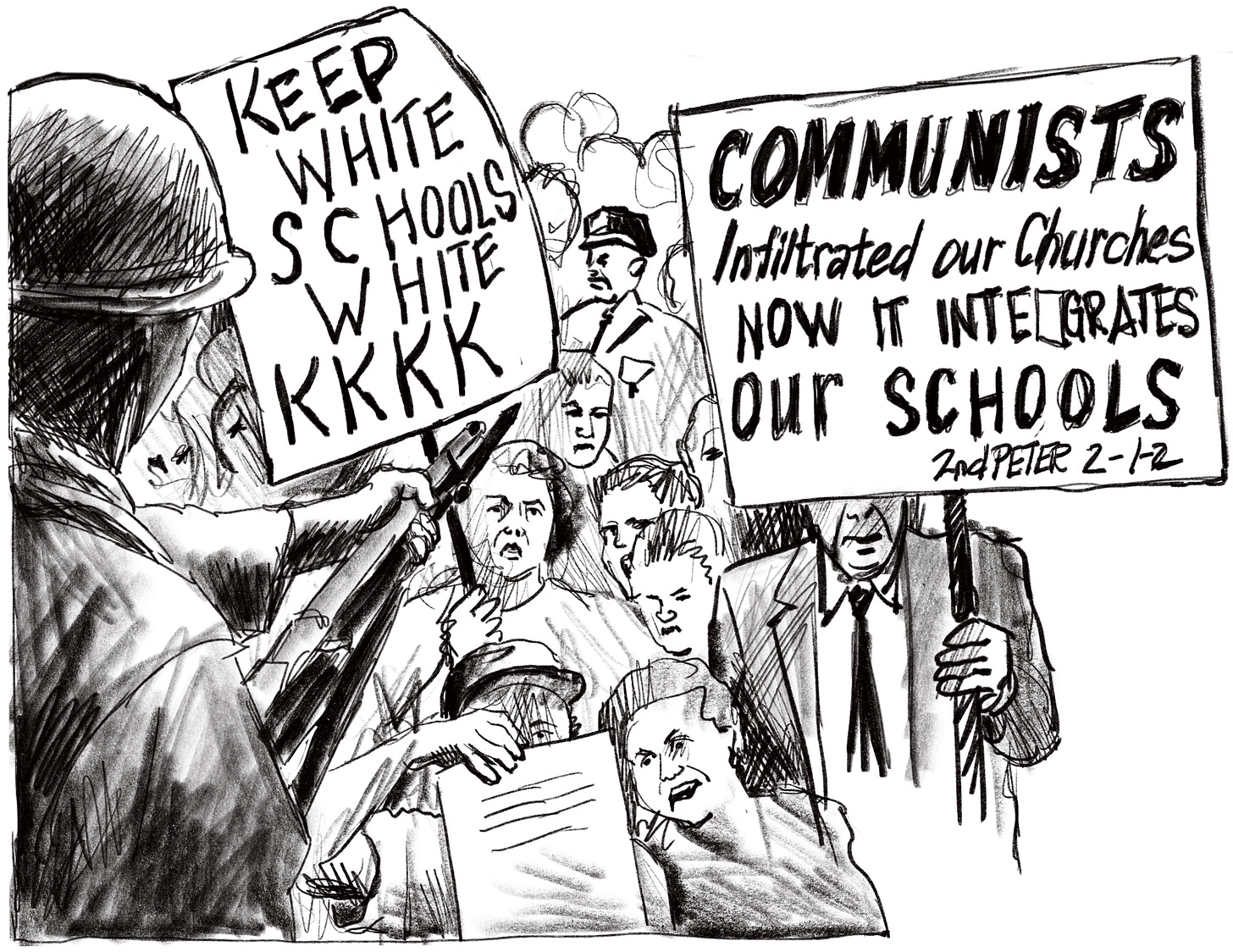

Carl’s unit was outside on the perimeter of the crowd, as whites screamed and waved signs that said, “Race mixing is Communism.”

Carl’s unit was there “as a deterrent to whites doing something violent,” and told to “expect anything at any time.”

Peaceful negotiations with the Governor had failed. The NAACP had chosen around 150 black kids, on the basis of grades and attendance, as possible test subjects – to force integration policies. Carl remembers seven students that first day though historical accounts say nine students were chosen. They’d been trained and prepared by the NAACP “to make an example out of a place,” Carl said.

“It was overwhelming, and more confusing than anything. I started looking at those kids and wondering how I would feel. I wouldn’t want to be in their shoes.”

Over the next 19 days, confrontation and rioting continued. On the 24th, President Eisenhower nationalized Carl’s unit into United State Army, into the 101st Airborne, that famous elite paratrooper division of WWII fame.

Now his unit was charged with protecting nine black students from Governor Orval Faubus and hundreds of raging white, distorted, spitting faces.

Carl was there.

On the 25th, troops escorted nine black students inside.

Carl asked himself why. “Why force black kids into this kind of trauma just to make a point? They were scared,” he said, remembering chaos and hurled hate.

Carl was assigned to a hallway where each soldier stood with a red and white riot club, forbidden to speak to students. No cameras were allowed. Describing it as a typical high school, except for the verbal abuse and the black students escorted everywhere but the restrooms. He wondered what the girls had to endure in those restrooms. Though there was physical violence, he never personally witnessed any.

He said, “How racist and vulgar people can get. It made me grow up pretty quick.”

Carl was at Central High every day for 3 months until he was ordered to return to his own high school. The 101st Airborne was there for the entire school year. Little Rock schools weren’t completely integrated until 1972.

“People are people,” he said simply. For 25 years as a railroad man, he’d hired for racial diversity, women, military on an equal basis. On the Roseville project, he interviewed workers on the tracks and in the trains, and as a result, built a facility that paid for itself in 2 ½ years. He had learned to listen to what people have to contribute.

Central High taught Carl that “an antidote to racism is opportunity, one person at a time,” he said.

Sacramento, 1957

I grew up in the same era but at age 10, I had no comprehension of segregation. Post war Sacramento was relatively integrated as a result of all the surrounding military bases, but the families of my black friends had to find white friends to buy their home, my mother told me later. Redlining.

What does a 10-year-old know about redlining? About gerrymandering?

By 6th grade, some of us played spin-the-bottle, and they played, too. I’m sure I knew our skin was different but I can’t remember caring. By the end of 6th grade, though, They refused to play and wouldn’t say why. It was years before I figured it out.

The bigotry was more subtle–then.

My dad was Jewish and my mom was not. Her Nordic looks caused people to speak unfiltered; they often revealed their anti-Semitism. I didn’t even know what Jewish was until a kid pulled a chair out from underneath me in junior high school and I landed with a thud on my butt on the floor. I remember so clearly. I looked up and asked him why, and he said, “Because of your last name.”

Now, on March 22, 2025, my daughter, her Canadian husband and their five fabulous children had been planning to move back to Toronto to be with his aging parents. Now, she says, Canadians are being vilified, even arrested, and they’re moving back for a terrifying reason.

And I ask myself, “What now? and Why?”