Introduction

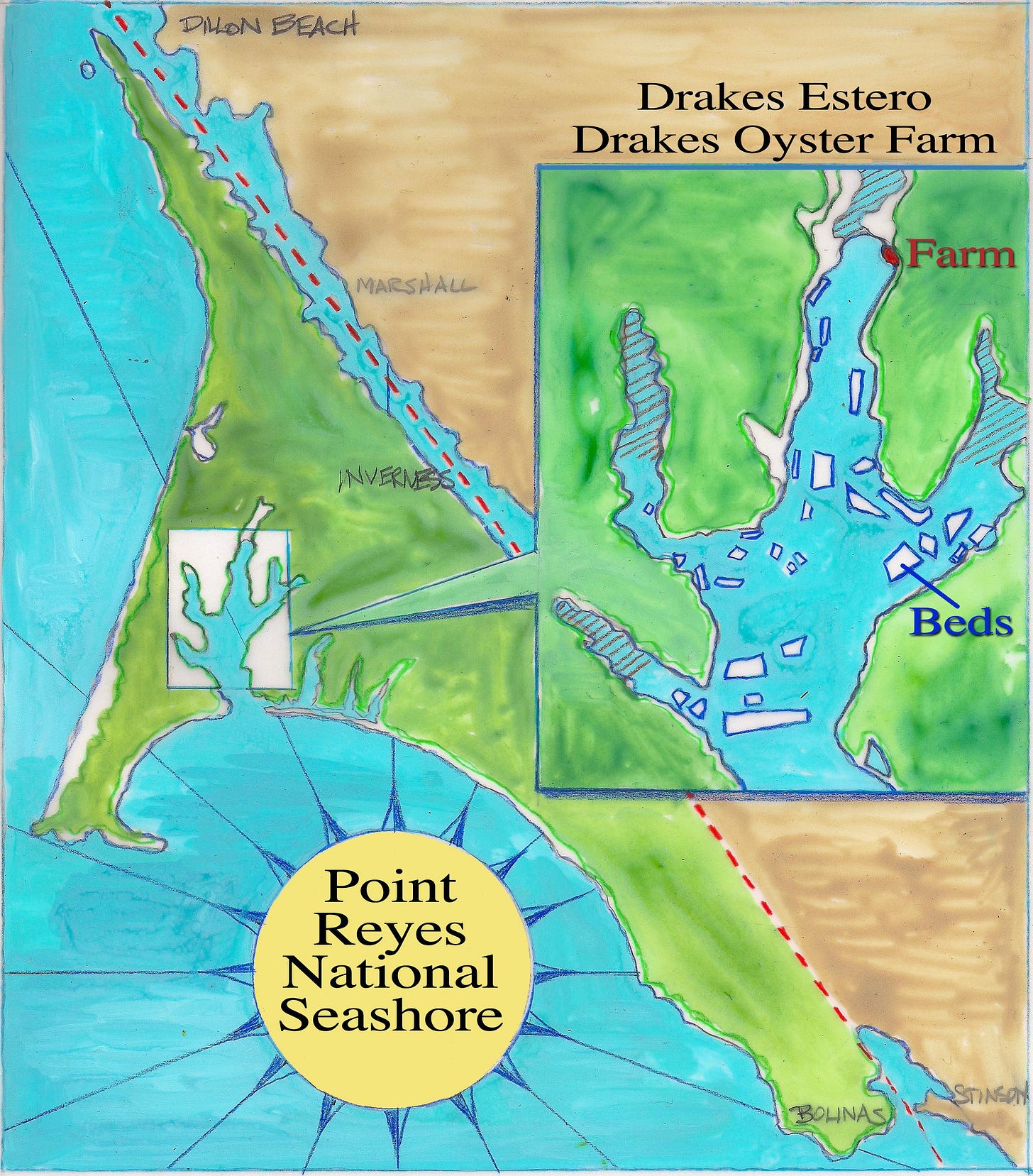

Fractured by the San Andres Fault, Point Reyes is a peninsula ripped from the California coastline. Moss hangs from trees in dense woodlands and high on the crest, wind-blown ranch lands offer breathtaking views of the Pacific Ocean. To the south, Drakes Bay remains pretty much as it must have looked in 1579 when Sir Francis Drake arrived. Some believe he repaired his ship in its calm estuary. In its tidal flows, oysters grew and thrived naturally.

2025

The silence and beauty of this place belies contentious and complicated issues and emotions. Lawsuits have flourished and now, after decades, is there a clear winner or even a clear compromise? Though I first came here in 1974, it’s not like I have any particular right to feel nostalgic about this place; I haven’t had the opportunity to visit all that often, though not for lack of desire. Even before I knew anything about wetland estuaries and how unique and critical this one was, I was drawn.

Winter 1974

The Point Reyes has always been one of those California places, so close to the heart, so quiet, so calm. My mother and I visited Johnson’s Oyster Farm, on the freshwater end of Drakes Bay. Oysters don’t come any fresher. She held one to her lips, slipped it down, and offered me a precious taste of pungent sea.

I tried, I really did, but it took me several years and visits to this wetlands estuary before I acquired an appreciation for such a raw and slimy substance.

Spring 2013

Edited version published Opinion, Sacramento Bee May, 2013

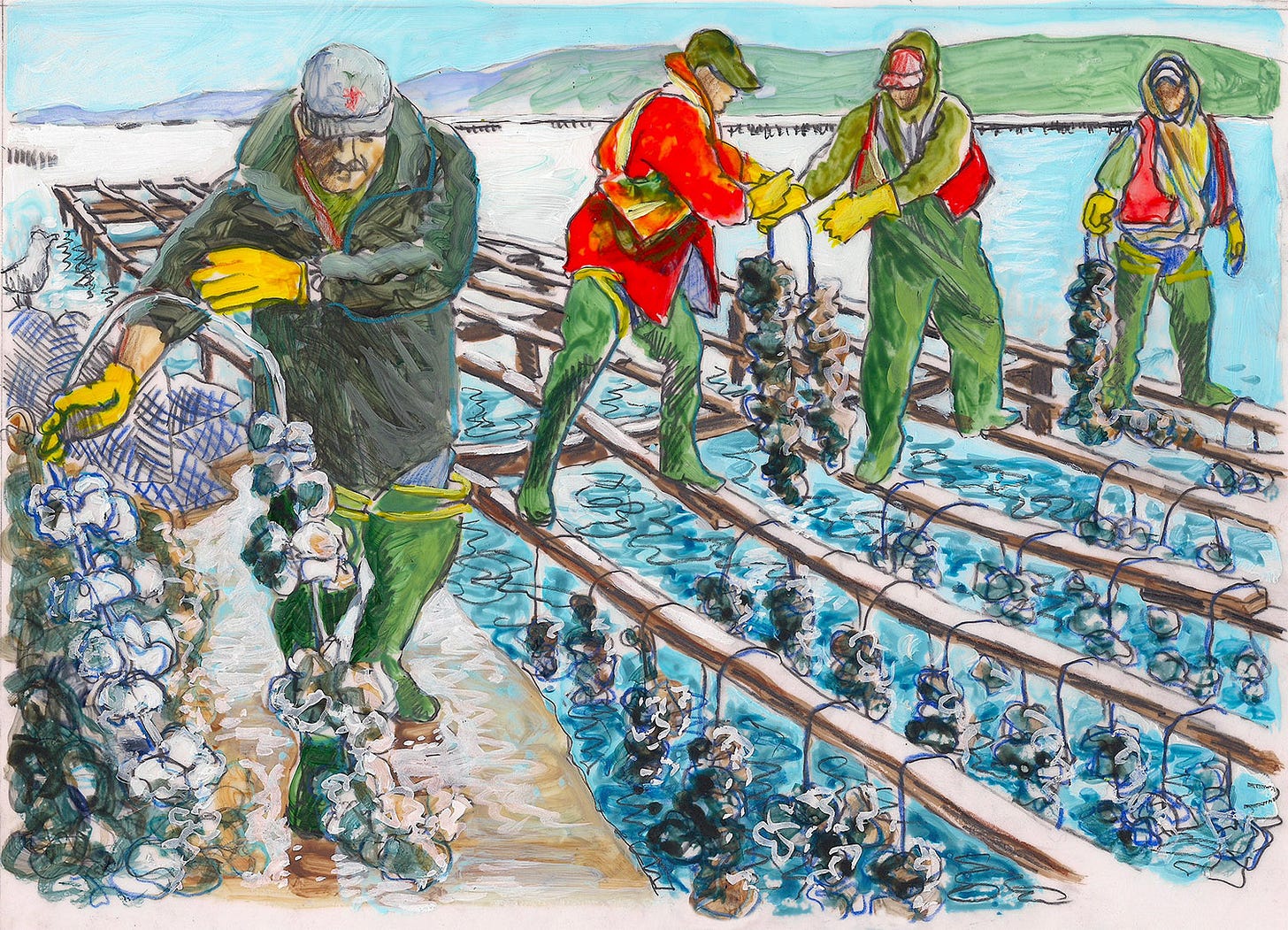

It’s early morning at Drake’s Bay Oyster Farm and the tide is out. I’ve asked the owner if I can hitch a ride. Oystermen push an old wooden boat from a rickety dock and leap aboard. Their leathered faces expressionless, lost in thought, hoods pulled tight, settled down into the chill and the hum of a small outboard engine.

Their day will be long, their labor tedious, their futures uncertain. We head toward the sea, to the oyster beds. From far away, they appear as long dark lines in a landscape of greys, hovering like a mirage on the water.

Approaching the first bed, clusters of mature oysters dangle from a grid of sagging boards. Other beds lie scattered on the shallow bottom in mesh sacks. There are 19 million oysters out here. More than 50,000 people visit the oyster farm every year to feast and to learn about sustainability, biology and marine agriculture. 500,000 oysters are consumed, rich protein grown with no fresh water. The oysters here generate both tourists and connoisseurs.

In a 1961 economic report, the National Park Service acknowledged the “public value” of the oyster farm that “presents exceptional educational opportunities.” Times change: power of the environmental movement has grown. In 1964, the Wilderness Act passed, and the Park, which owns the land under the cannery, declared that the estuary should be protected as “an area untrammeled where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Oysters became a high demand, high protein value food source during the Gold Rush. Commercial farming had been formally permitted by the federal government for almost 80 years. When Johnson, the owner then, sold his five acres to the Federal government in 1972, he signed a 40-year lease to farm.

When Drake’s Bay Oysters, owned by Kevin and Nancy Lunny, acquired Johnson’s business in 2005, they knew that the lease was due to expire in 2012. They asked the federal government to extend the lease, to continue harvesting shellfish. They argued that the estuary should remain “potential wilderness,” and that they be allowed to operate, pending the outcome of litigation.

Tying the boat to the oyster racks, the men step cautiously across the narrow wooden boards. One man lifts a batch of oysters strung together on a wire like a necklace. He passes it to another man, who passes it to another, until a small barge is piled high.

About an hour later we’re back on shore at the cannery, where they’ll spend the rest of their day sorting and packing. It’s a timeless process, this plankton to protein, this touch of human hands from seeding to sorting. As filter feeders, the oysters help keep water clean while a diverse ecosystem has responded, surrounding the beds like a reef.

Winter 2015

After several years of litigation, the court denied an extension of the lease. The farm closed down at the end of 2014. Decades of collaboration and shared cultures ended for the Lunnys and the farm families. The Park Service began removing what remained of the cannery.

On January 3rd, a few hundred Point Reyes residents gathered for a potluck. Huge barbeques were covered with the very last of the freshly harvested oysters. Family and friends celebrated the history of the oysters, and at the same time, looked forward to a different kind of future.

Fall 2016

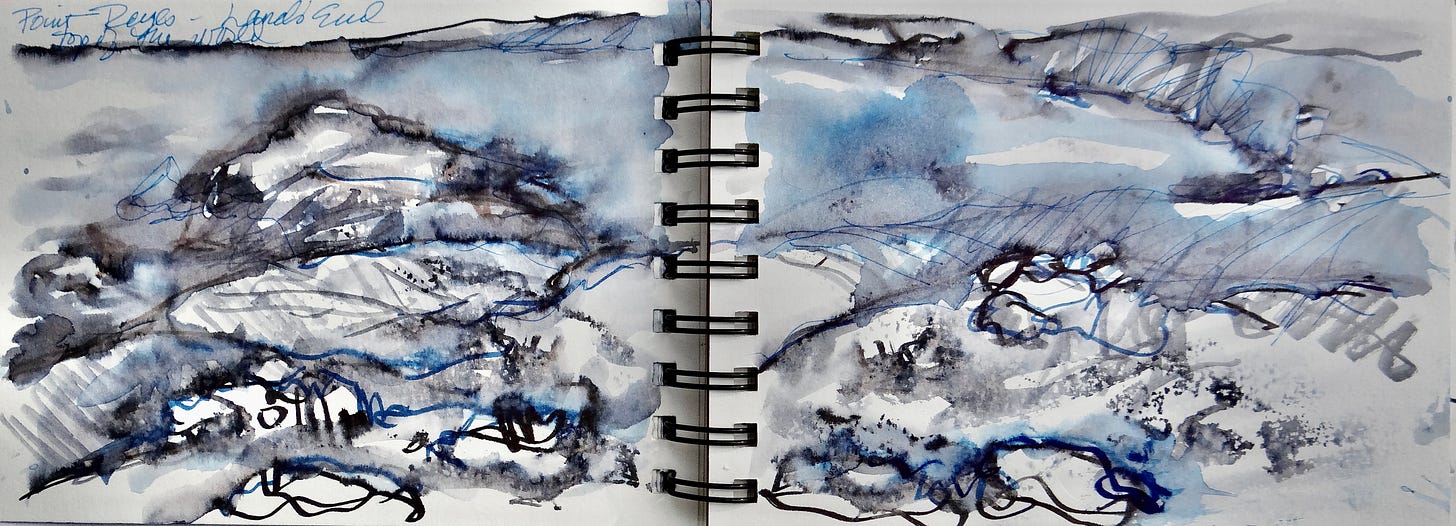

It’s a rare day that water is smooth out here. With overcast skies, wind is nil, air temp perfection between warm and cool. Evidence of last phases of removal and restoration: some earth moving equipment on the shore, and a few ghostly wooden structures just below the surface of the water. A flock of white pelicans float by. I wonder if they miss the bounty of the farm.

What is it about this place?

It might be how flat it is.

A narrow gravel road, dusted with crushed oyster shells emerges from primordial forests. An estuary reveals water interspersed with clumps of saltwater grasses. Green, blue, green, blue, Kelly green, sky blue. This is eelgrass, one of the aspects that makes this place unique. Tide has pushed dying eelgrass upon the shore, each thin tape-like blade covered with tiny hopeless dots of barnacles that won’t survive. But across the bay’s bottom, millions more will.

It might be the quality of light.

I look far out to where I know the ocean waits. Light bounces off the surface, the bay looks so wide, so flat. Colors are subdued, soft.

It might be the quality of silence.

I’ve been out on this water with the oystermen on one afternoon and the following early mist covered morning. We only went as far as several oyster beds, wooden frames heavy with hearty, profitable, protein-rich oysters. And while former outboard engines were relatively quiet, it wasn’t as quiet as this.

I’d stood on the shore battling my fear of water–or rather of being immersed in bodies of water where creatures lurk with the “undertoad,” that mythic ‘70s monster of Irving fame. Anything that lurks on the bottom used to terrify me, against all reason. In a sea kayak, you can flip upside down, with an urgent need to expel yourself from a tight space.

This day, this lovely day with an expert guide behind me in a tandem kayak is a small step towards addressing this fear–of water, of currents, of unrecognized forces that might carry me where I don’t want to go.

With only the sounds of paddles cutting into and lifting water dripping, and an occasional pelican cry, we head towards the mouth of the estuary, gliding over eel grass gently waving below. And blessed we are, making great time towards the mouth of the estuary, gliding over eel grass gently waving below, and a small stingray, wings rippling.

Soon we hear the barks of sea lions on a spit near the surf. We stay far away, beaching the kayak in sand where Sir Frances Drake may have walked.

July 2017

Today I see Drakes Bay only from the shore. All evidence of the former cannery is gone except for bits of oyster shells brought by the tide to the beach. The dock, buildings, and workers have disappeared, along with picnic tables where customers enjoyed a unique experience of the freshest oysters possible along with an opportunity to learn about sustainable agriculture. The estero as it always must have been. Is there a breeze? I don’t remember.

2025 update

I’ve only recently been learning about the current status of Point Reyes. When I went in 2013, I wondered why the Park was so adamant about the oyster farm. What’s next–the ranches? The answer is yes, cattle were next. Or are they?

“The cows didn’t want to leave.”

Is there more to the story than Tule elk versus cattle? Sadly yes.