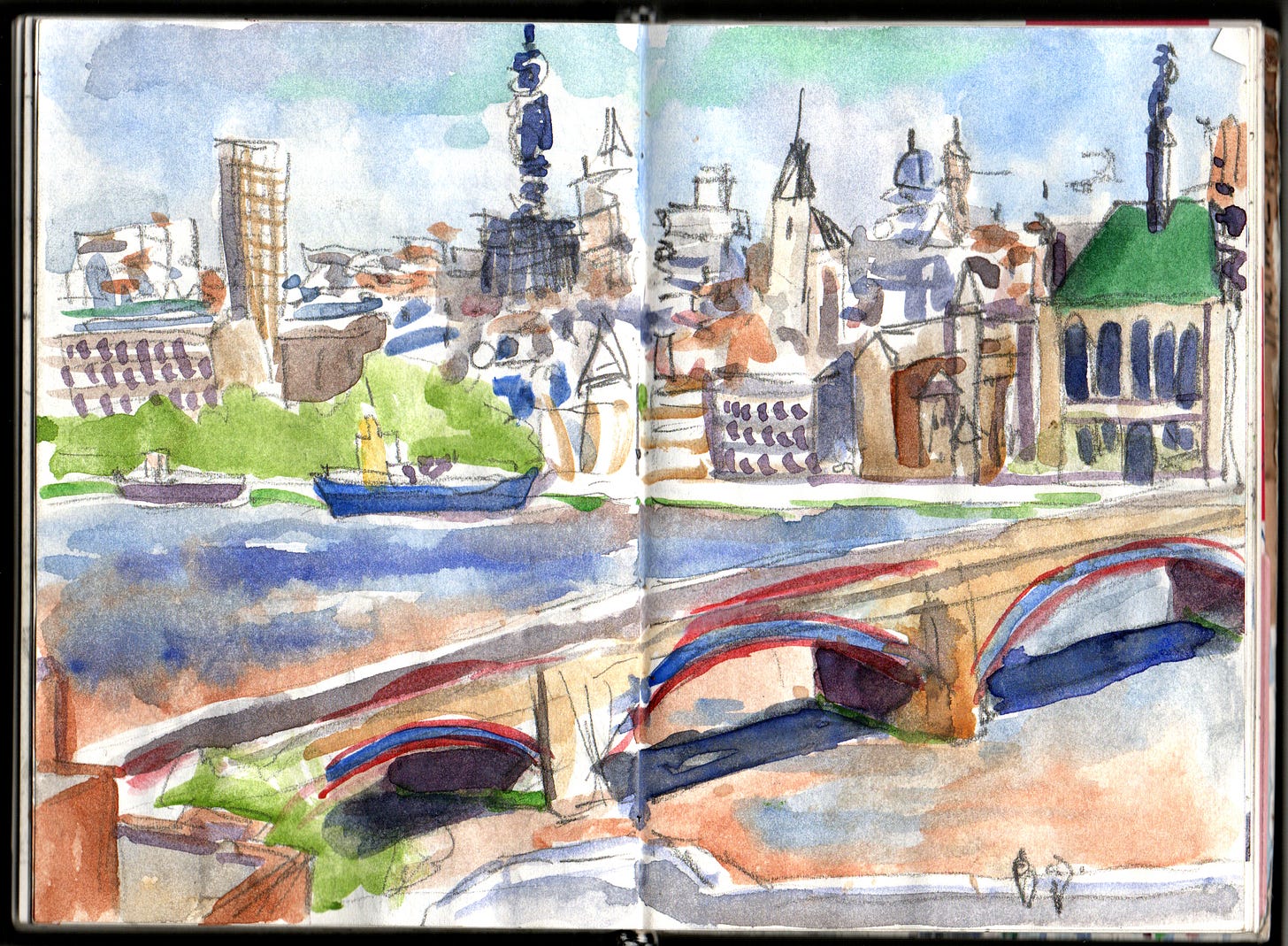

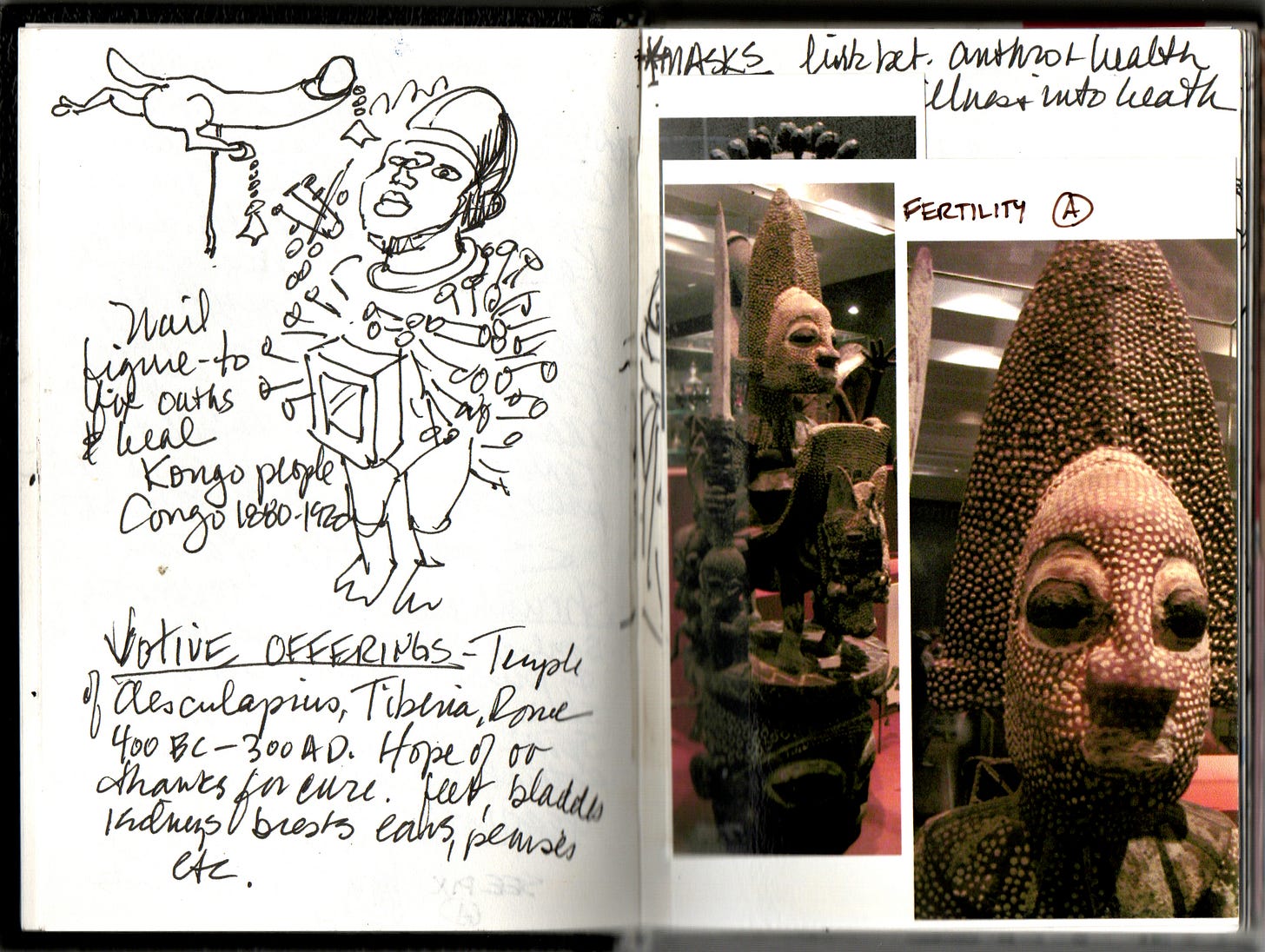

At the Tate Museum, London, in 2003, I was captivated by an exhibition of artifacts found in the River Thames during construction, saved and displayed as a “Cabinet of Curiosities.” I examined tiny items retrieved from the mud by volunteers and installation artist Mark Dion. Categories of objects were arranged meticulously in drawers.

I spent days wandering the artifacts at the British Museum, totems from other cultures that curators had “acquired” and displayed.

Fast forward to January 2019. I was scheduled to have an exhibition at a Sacramento gallery that June. I don’t like creating work for an exhibition for several reasons. One, my most rewarding projects relate to transforming the appearance of public spaces on a large scale, a passion influenced by an early career in advertising in image-driven LA. Second, the business side of my personality thrives on making a sale first (a commission), getting partially paid, and then delivering a project. Anything less is work made on speculation. Yes, that’s crass but it’s my reality. Third, I have to make something that means something to me; I’ve no interest in making pretty art, for example. Thus, I was doing a lot of thinking.

I’d inherited my parent’s house several years prior, a warm and loving home full of mementos and memories, paintings, antiques, albums full of other people’s lives. Too much stuff. I’d purged some and kept some, and was thinking about a series of drawings of these simple things that I’d chosen to keep and what each symbolized for me. One was especially mysterious and I have yet to explore it: stay tuned.

What follows is a project about what we retain when we lose, about objects that no longer appear to have value, except as memory: about resilience, reality, and adaptation.

In November 2018, a fire started in forested foothills near Paradise, a town 20 miles west of where I’d been born, in Chico in the Sacramento Valley. Two months later, I listened to a woman read an essay about her family who had lost everything in that fire, a fire so explosive and catastrophic that people fled for their lives. Her family had survived but nothing was left of two homes except things that had a higher burn temperature than that intense fire. I asked her if she’d collaborate with me on my June exhibition, “Simple Objects,” drawings and photography of everyday things–the things that survived that fire, in those two homes.

The fire began the process of curating, and as we poked through the ashes, we began to choose and to think about what we retain when we lose. She had her approach, an intimate and personal response. I, in contrast, came to the objects with the detachment of an observer. We were bound to come into conflict, sadly, and we did.

Time is accelerating along with change. When I think how quickly the first exhibition went, and then the second in Yuba City, and then–all of a sudden it was the end of 2019–and we all lost the world as we knew it.

By deconstructing a project that meant so much to me, I hope to understand the acceleration of change in the relationships between people and in the environment– what it means for the making of art, whatever that may be.