The Iconic Dungeness Crab

Dungeness crab is a California tradition, and now that I’ve seen what it takes to get them to market, I’ll never question prices again.

In November 2014, I began to research a California cultural ritual, the famous Dungeness Crab. Icon of Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, paired with the Wharf’s incredible sour dough, tourist and native alike used to flock there for a very special treat. When I was a kid, we dressed up to go to the City, to visit both my grandfather and the Wharf. It was part of being a Northern Californian.

No more.

Fisherman’s Wharf, Monterey, Bodega Bay and the Marine Lab, Moss Landing: I drove all over doing my favorite thing, talking to people and learning about California’s delicate balances.

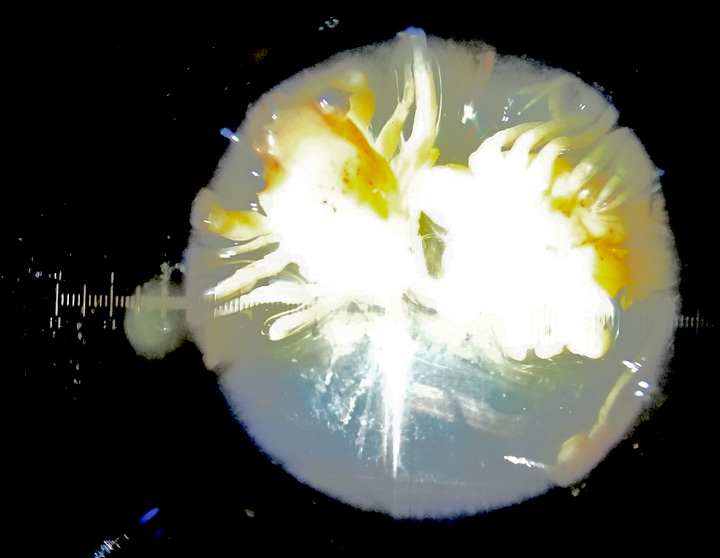

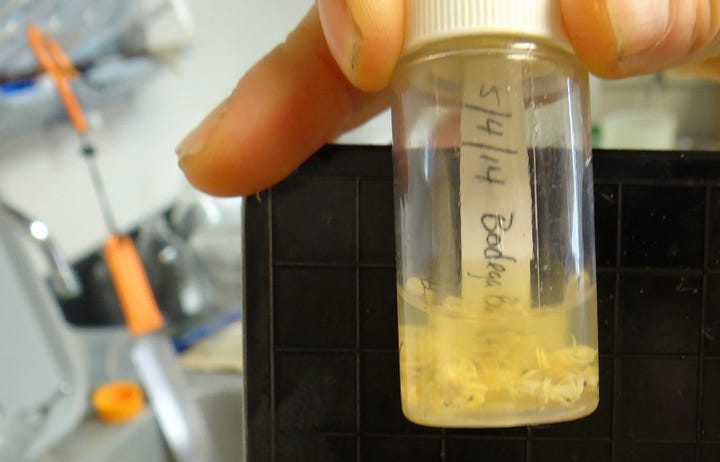

At the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, scientists showed me the life-cycle of these creatures.

At Bodega Bay’s Spud Point Marina, I found some fishermen.

From Bodega Headlands, the sea has a dangerous swell. Under an oppressively dark gray storm promising sky, massive waves crash into the windswept peninsula that protects Bodega Bay and the boats moored at Spud Point Marina.

The first fisherman

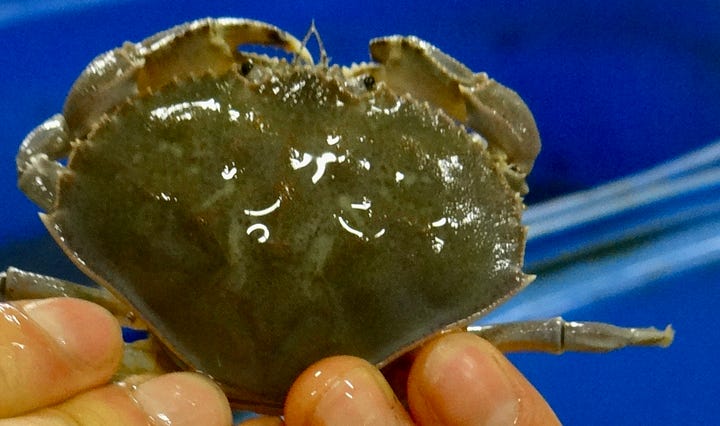

Captain Frank Terlouw prepares the Barbara J, a classic wooden fishing trawler, for a 4 a.m. departure to check and unload his 260 crab pots, no matter the weather. He and one crewmember will head north toward Anchor Bay and return 38 hours later with Dungeness crabs destined for holiday meals, a Northern California tradition.

It was a “challenge getting in and out of the harbor due to the big swell. It hit 22 feet while we were out. Not bad on the outside but a rough trip none the less,” Terlouw says in an email after returning.

His haul was 3,000 pounds of mature male Dungeness crabs. “It's been a good start to the season and this trip we got $4 a pound. Due to Christmas market. Yeah!” he wrote.

The second fisherman

In my naivete, I thought it would be interesting to hitch a ride on another crab boat. Jason Taylor blew into Bodega Bay on a violent storm in 1989, and never left. He warns that even getting in and out of the harbor can be terrifying, and invites me on board the Annabelle for a brief visit.

His face was etched with history, leather bound, rough around the edges. Busy on a boat, I interrupted him. He didn’t mind, and after my query that I was curious about the crab fishing industry in California, he invited me on board.

I followed him into a snug, overly warm cabin, a stark contrast to a chilly hint of rain and cloud filled sky. Getting ready to go fishing, he said. Just inside the door, foul weather gear hung red and yellow, pulled tight with bungee cords. On a narrow galley counter, groceries, cans of soup, bottles of water rested, recently unloaded. I squeezed onto a bench at a tiny galley table.

He introduced himself. He looked older than his forty-six years, the sun, wind, and I guessed more than a few years of very hard living. A full head of dark hair matched a neatly trimmed beard. He wore copper bracelets on both wrists, sleeves of a cobalt blue tee pushed up, and an earring in his left lobe. He wasn’t a big man, not as big as I thought a fisherman ought to be, though solid, not beefy, with obvious strength in wrists, arms, neck, and back.

He looked a bit like what a pirate might look like, graced with the air of a rebel in blue jeans, a stereotype, a non-conformist, a living-on-the-edges-of-society, itinerant kind of guy.

He confirmed this in degrees, starting with how he began fishing at 21. Working at a Kmart somewhere close to a harbor, he paused to watch squid boats heading to sea. He had an epiphany, went to the docks in Monterey and signed onto a sword fishing boat.

This is how he learned to fish, infatuated with the challenge of landing 400 pound, thrashing swordfish.

This is how he learned to listen, he said, and I thought at the time, what an odd thing for a fisherman to say. Listen to what?

He had blown into Bodega Bay on a violent storm in 1990. Eighty miles off Point Arena, it had taken three days to find safe harbor, twelve hours straight at the helm. Exhausted, he staggered to the nearest bar, and has been crewing for local fishing families ever since. Except for the ten years he worked as a painter after the trauma of loosing seven friends to the sea–in six years.

We stepped out of the cozy cabin on to the impossibly cramped deck so that he could demonstrate how he catches California’s famous Dungeness crab. The season had just started, and he was enthusiastic about prospects for a year of abundance, including high prices. Most years are a struggle he said, to meet the needs of a precious young daughter, to pay rent, to keep his car working, paying his mechanic off on the honor system. He lived 20 miles away, 10 of them along the steep cliffs of scenic Highway 1.

At the stern, crab traps were piled four and five high, starboard to port. He showed me how he attaches plastic bait traps to traps, identified by uniquely colored buoys. He bent over, and with his knees, lifted a trap to his thighs, and then higher, to show how he hurls them overboard, at 120 pounds empty. I couldn’t lift one past my thighs.

He showed me the mechanism that pulls the pots up at 6 feet per second, weighing over 400 pounds full, demanding a man’s unfailing focus. He’ll catch 7,000 pounds of crab in two days, often working 18 hours straight. He pointed to pole structures, standing like sentries on each side of the mast, that descend at 45 degree angles to stabilize vessels, and said that overloading can roll a boat, pots can pull men to deep deaths. 98% of the accidents are caused by human error, he said.

He was a cowboy in Texas and a sheet metal worker in San Francisco, but he loved fishing and the sea. “It’s peaceful,” he said. “I wake up every morning at 4:30, put my boots on and look forward to an adventure.” He sighed. “I leave my problems on the dock.”

My essay about Dungeness crabs, including his contributions, appeared in the Sacramento Bee the morning of December 28th. I didn’t try to contact him. I didn’t want to bother him if he was fishing.

At 9:25 that evening, this fisherman drove his car off a 75-foot cliff, just north of Bodega. The officer who tried to stop him for vehicle equipment violations said he “appeared to accelerate” straight over, and made no attempt to stop. I dedicate this essay in his memory.

Listen to what, I asked myself. What had this man really said?

Back at the dock, cranes lift containers off decks to waiting tubs full of angry crabs.

Crabs tumble en mass into aerated, circulating water, claws clacking ferociously. Brokers distribute them to be sold live or cooked. The 2011/12 season broke historic records with a catch of almost 32 million pounds at an average of $3 per pound. Though 90% of legal size males are caught each season, it’s a productive industry managed for sustainability, and this year is promising.

Stacked artistically in rows upon beds of ice, I buy some for dinner with a friend. And now that I’ve seen what it takes to get them to market, I’ll never question the prices again.

Then and now.

In 2014, experts said that Dungeness crab season normally began in mid-November with the tasty Crustaceans reaching avid consumers at the start of the holidays. That’s not happening this year. Again. Oceans are changing. Visit CA Fish and Wildlife for latest information from experts in their fields. Migration habits of whales are also changing, following food closer to shore, and this is also a factor in the late start to the Dungeness season. As always, life in California is a delicate balance.