On a Tuesday morning, I walked into a conference room full of strangers, eight well-dressed men sitting around a conference table at the famous Roosevelt Hotel on Hollywood Boulevard. Site of the first Academy Awards, Clark Gable had danced up and down the stairs with Shirley Temple. The recently renovated Mission-style architecture, crowned with a cupola and an immense sign overlooked Hollywood’s sidewalk of stars, Grauman’s Chinese Theater, and the Hollywood sign.

Hollywood was a slum when I lived there in 1967. Fifteen years later, it remained a slum. Celebrities stayed at the Roosevelt, but hookers still lingered along the infamous Boulevard.

I’d gotten a call from an LA designer just days before, asking that I design a mural, and jump on a plane. So here I was. The client motioned me to a seat on his right. We shook hands, and I slid the sketch to him. He glanced at the sketch and back at me. He said, “Boy, you really know how to crank this stuff out.” I looked him in the eye, around the table, then back to him. From some mysterious place deep inside me came a reply, “You show me a whip and I’ll do anything.”

He laughed, I laughed, I looked at him, at all the other men. We all laughed.

To this day, I have no idea what inspired me to say something so outrageous to a total stranger, much less a new client and his minions. Intuition perhaps.

The client was a short, portly man, a cross between Pavarotti and Bacchus, with appetites to match. Rumor had it that he owned hotels in Atlantic City, Pittsburgh, and New York City. He had a team of accountants and contractors, and his goal was to update and upgrade this stunning property, in the hopes that Hollywood Boulevard would transform from a tawdry present to a shining future.

It was a long shot. I’d lived in the hills above the Boulevard in the late 60s, years of Eldridge Cleaver, Manson murders, peace signs, “Hair,” and when one joint of weed meant jail. I’d lived in LA for 17 years. I knew LA, from Beverly Hills to the industrial heart of downtown, to the beaches. I’d lived on the infamous Bundy Drive of OJ when he was a college icon. I’d met Nicole Brown Simpson briefly at a Halloween party, one of several beautiful blonds who were comparing rare jewels on their sparkling hands. I had no idea who she was and nobody there knew what was to become of her.

The Roosevelt was notorious, home base for major and minor celebrities, from aging to aspiring. It was a place of contrasts. At the front desk, an old rock star banged his fist on the counter, and demanded loudly of the young desk clerk, “Don’t you know who I am?” Conversely, Ted Turner quietly checked himself in. Events brought old stars like Danny Kaye and newer ones like Whoopie Goldberg.

My project began with a mural in a hallway between the main hotel and the pool area. It was a dismal space, so I took to transforming it with enthusiasm. My teen daughter was with me one day. She had been asking me to get autographs from celebrities I saw, but years before stalking paparazzi I’d lived in Beverly Hills when people respected privacy. When the entire band of Blood, Sweat, and Tears walked through on the way to their rooms one day, I called her to suggest she come down and ask for their autographs herself. She said, “Who?”

Clark Gable and Carol Lombard paid $5 per night to stay in the cupola penthouse at the very top of the hotel. The owner invited me to follow him up a spiral staircase to see the lavish suite and he said gesturing, “This is where they slept, and that was their bed,” and continuing as I was getting nervous, he said, “And those were their sheets.” Not communicating my trepidation, I said, “That’s great. Thanks for sharing, but I’ve got to get back to work.” And fled before he had a chance to reply.

The owner, being a man of diverse interests, often flew to Alaska to hunt big game. He’d invited his hunting guide to stay as a thank you and had introduced me early one morning. Later that evening, I found the hunter in the elevator with, I assumed, an escort. He was confused as to how to get to the concierge level. I rescued both the hunter and the hooker.

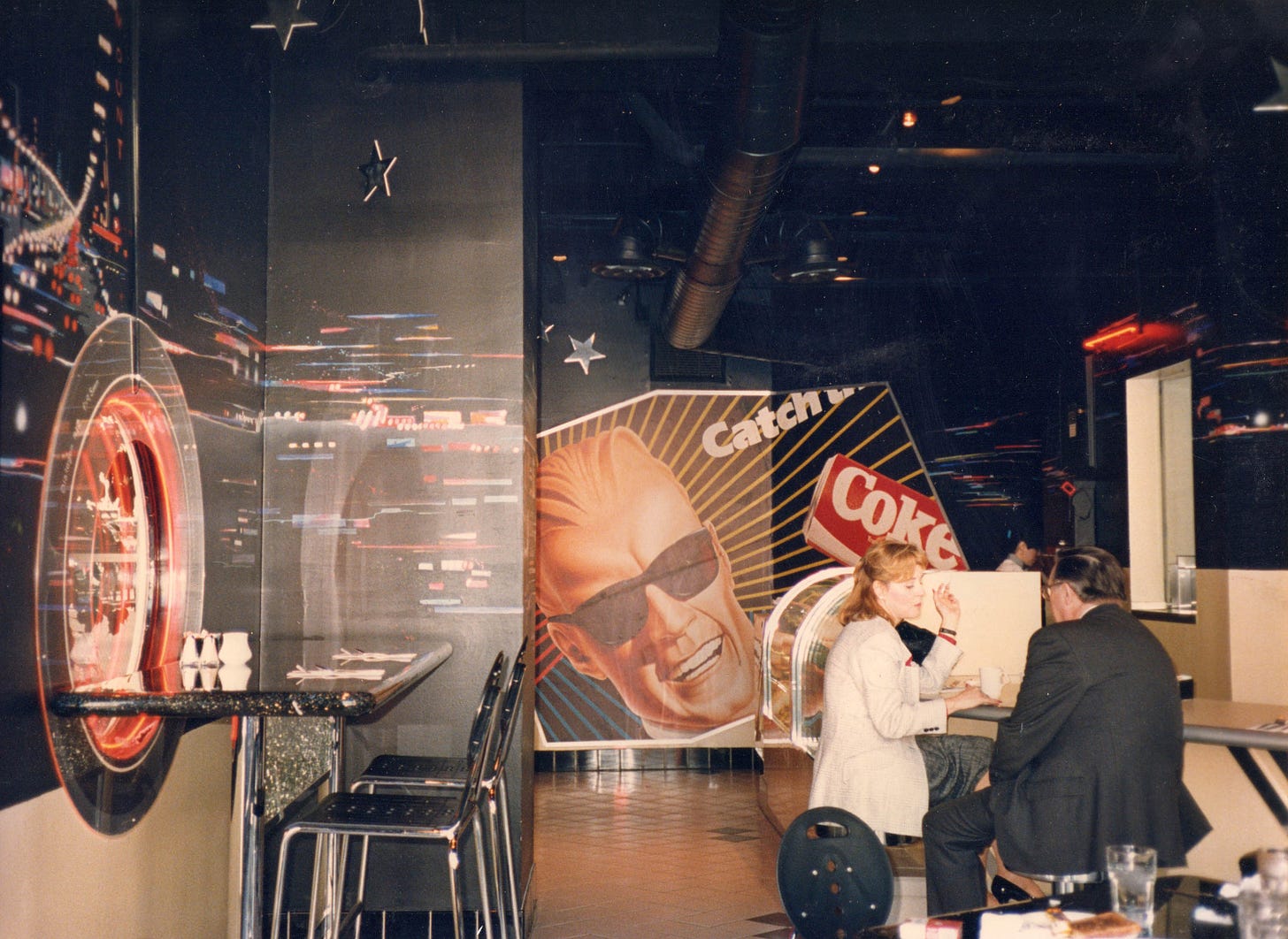

I worked on this $35 million renovation project over the next two years, flying back and forth between Sacramento and Los Angeles. I created murals and paintings for guest rooms including the Presidential suite and an entire restaurant.

One evening, I was sitting at the bar chatting with the accountant. We were talking about my current commission, a series of thirteen 42 x 60” paintings on paper. I said something like, “I trust you,” and he looked me straight in the eye and said, “No, don’t do that.” A month later I got a letter that the owners had declared bankruptcy. I wrote back saying that if they didn’t send the balance owed for the 13 paintings in process, that I’d keep the 50% deposit and the paintings.

What had I really said to that room full of men that first meeting? I never heard from them again.