Tuscany 2012

With curiosity, sketchbook, and paints in hand, I drift through a place that insists on a slower pace.

I get an email from an old boyfriend, way back from the first time I left my husband. He’d always been one of those men who collected women, but also kept them as friends even after the romance had ended. We’d kept in touch as well, and he was the architect on a house we built in Manhattan Beach. Great guy. Lots of fun.

I had a theory as to what had happened to him in the 30 odd years since I’d seen him. My theory turned out to be true but I’ll skip the details. So here he was, about to get married for the Xth time if you count all the significant relationships, inviting me to his wedding in Tuscany. When I declined he said,” Well, we have an apartment below our place and you’re welcome to stay as long as you like.”

Wait, what? So I said yes, I’d love to come, not for 3 months, however, but how about 5 weeks? I figured if we each thought the other intolerable, I’d just leave and travel on my own. So I went. I stayed. His wife was gracious. It was glorious, despite his remark one day that no wonder my marriage failed: I was so hard to get along with. (Read “you’re not doing what I tell you to do.”)

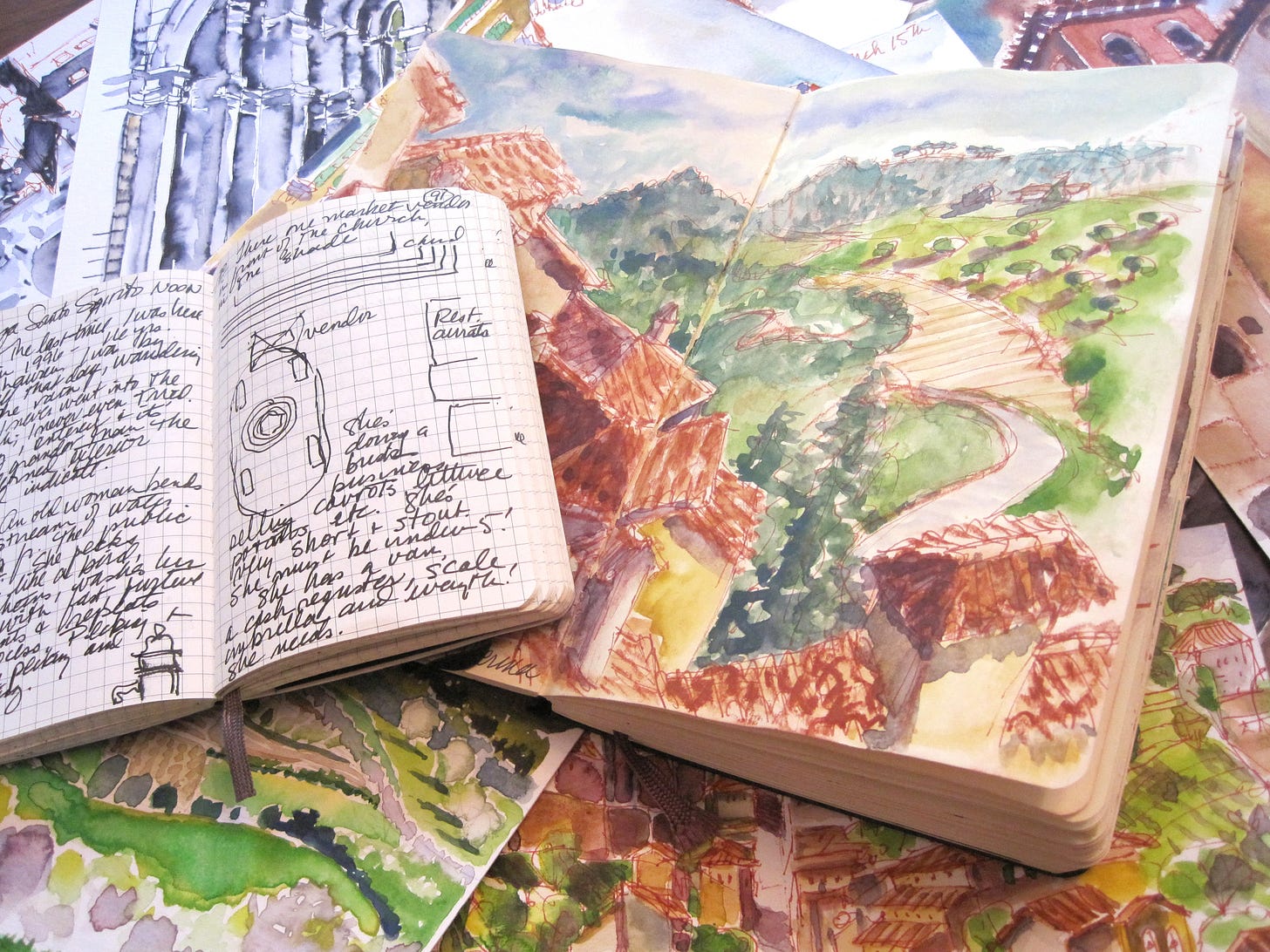

When I returned, I wrote about my experiences for the Sacramento Bee. I revisit an early draft here, with some edits perhaps, interspersed with sketches I made there.

A gift of time brought me to a hill town in Tuscany for five weeks in the middle of March. Sixty-five miles southeast of Florence in the Apennine Mountains. an old, straight Roman road crosses a flat valley and ascends to a hilltop town. Anghiari spills from a medieval fortress, across ridges and commands stunning vistas in all directions. I’ve come here to find out why artists, writers and travelers crave an understanding, a search for sensations and connections, from this ancient Etruscan place.

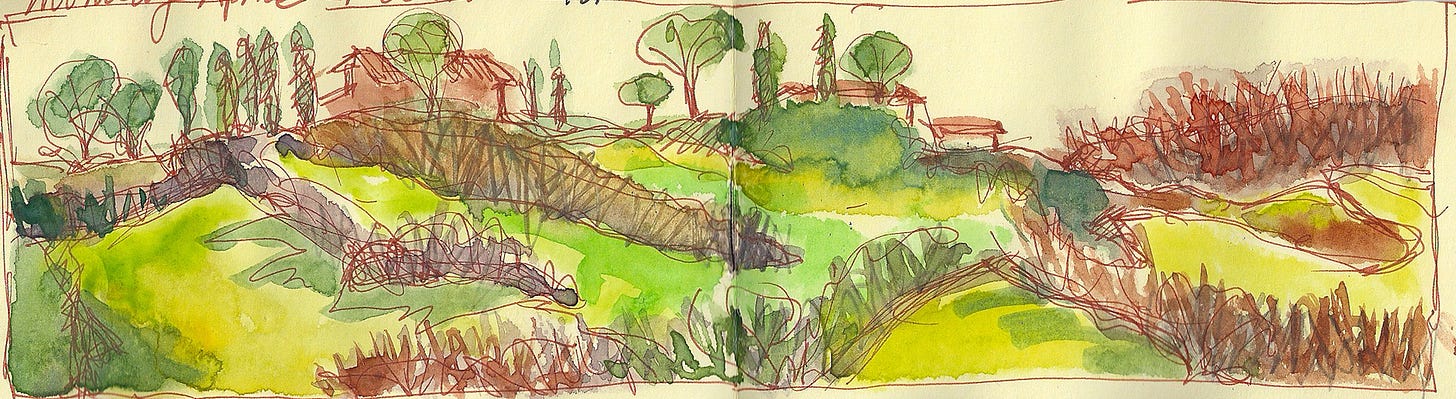

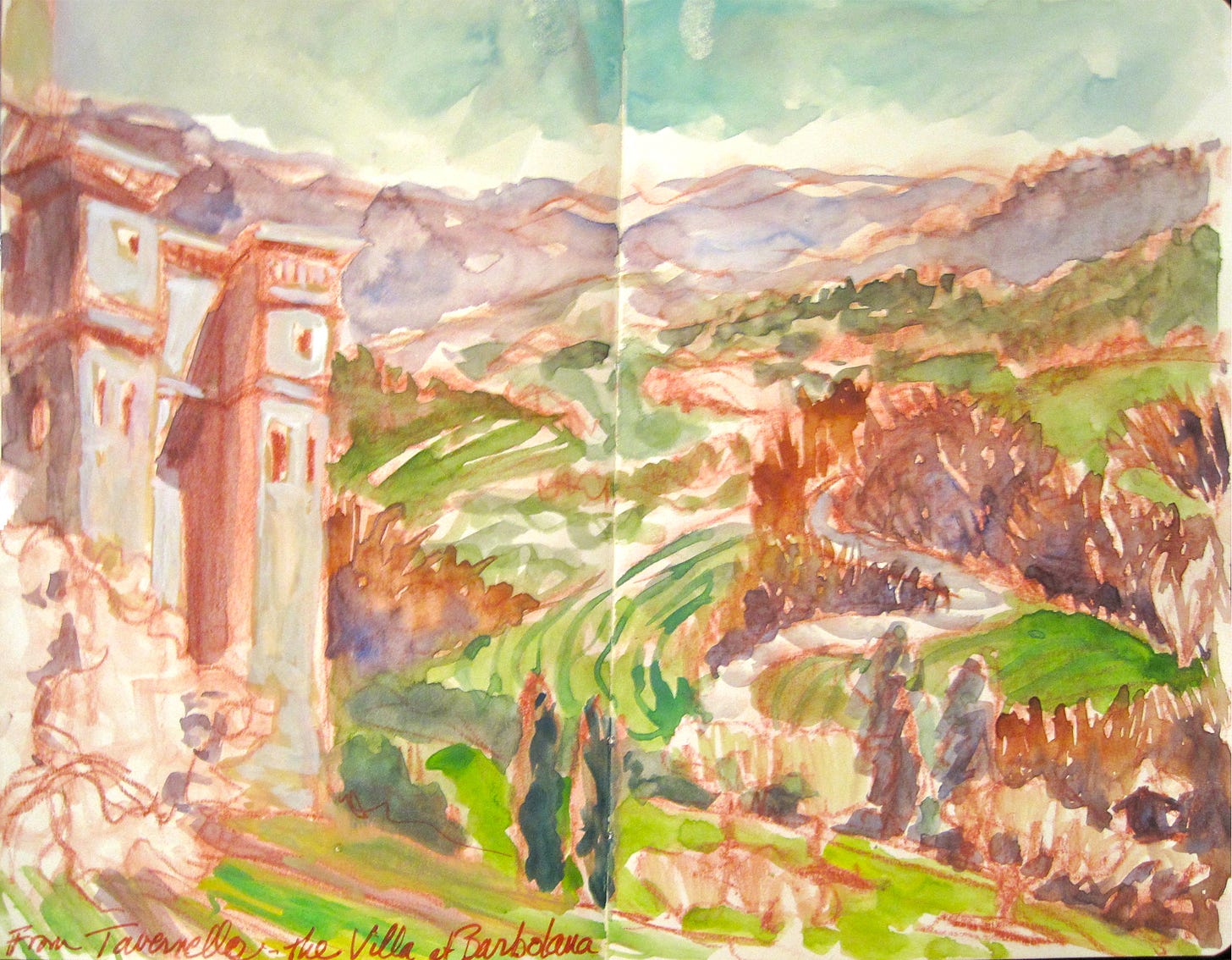

Just as winter slides into spring, Anghiari provides a perfect base for exploration. Bare forests contrast starkly with verdant fields. Cypress, umbrella pines and olive groves stand tall, their forms repeating in a winter palette more luscious in texture than color. Fields of red poppies and yellow sunflowers won’t appear until summer. Knobby hills protrude through alluvial valleys. Like the ancient Etruscan settlers, we feel secure on top of the hills. The Etruscans chose hills for defense, and because breezes keep mosquitos away. Vast forests of pine and chestnut cover distant hills. On their crests, the line between sky and forest is indistinct, blurred, a fuzziness that adds softness to a landscape that transcends beauty.

On past visits, I traveled in Northern Italy by car, hiked in fear the steep cliffs of the Cinque Terre above the Mediterranean Sea, and have happily gotten lost in Florence. I’ve seen photographs and paintings to the point of cliché. On this trip, I wander the countryside. At a party one evening I drift away, down a lane to a neighboring farm. I watch the farmer in a red tractor turn up large chunks of moist brown dirt in a small field, back and forth, back and forth. It is in the fragrance of his newly turned earth, an earth of antiquity, that I can feel the magnificence of this land.

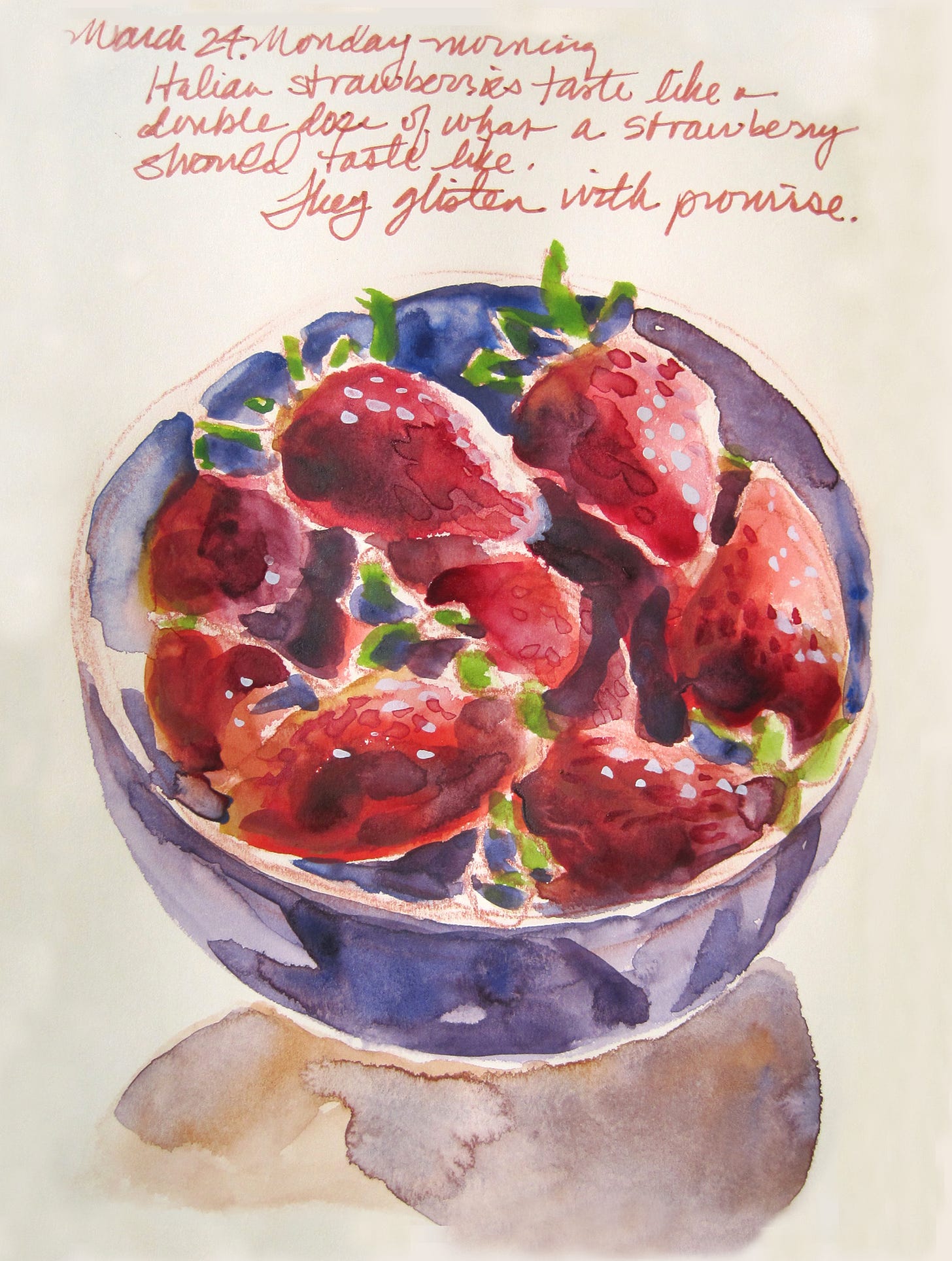

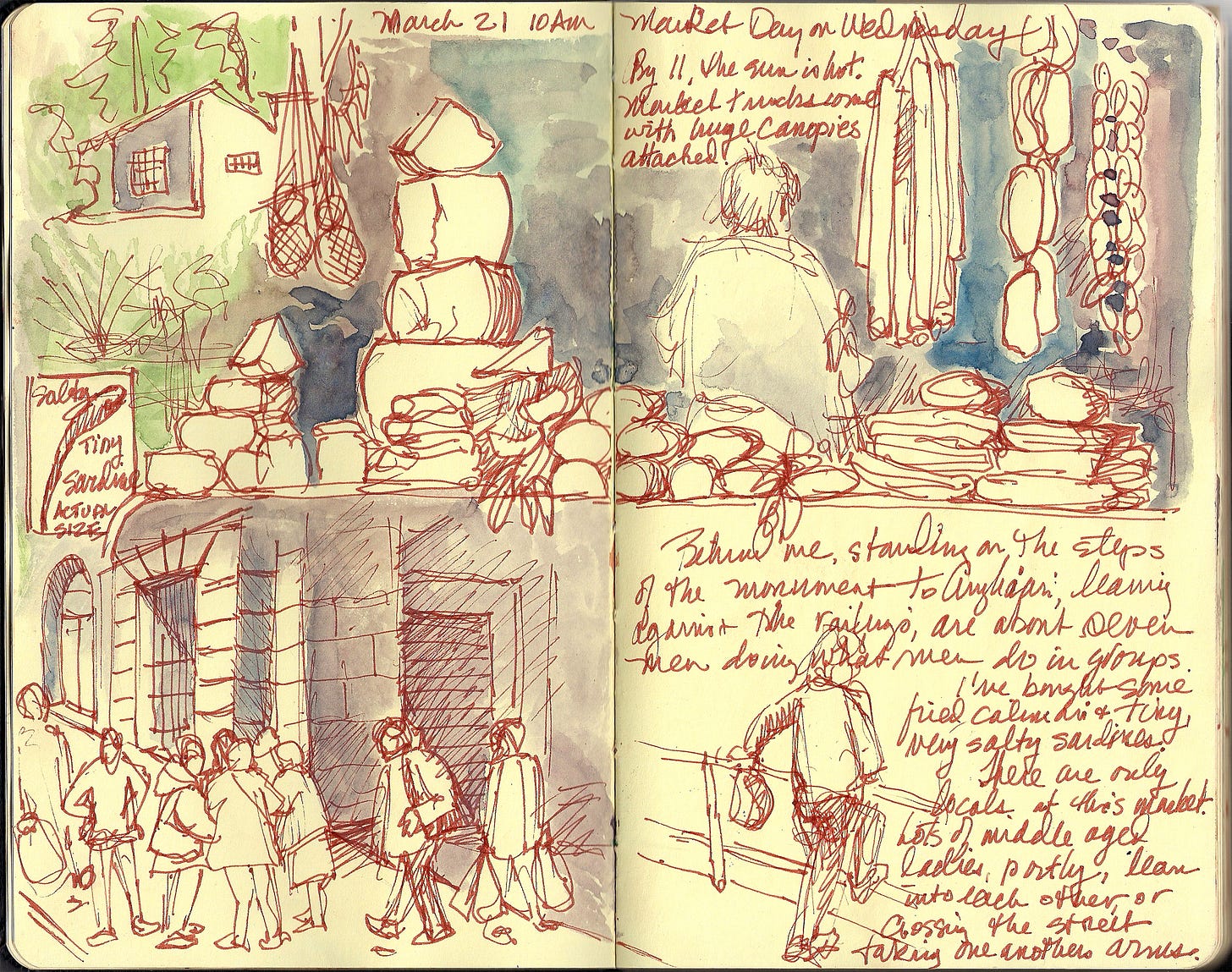

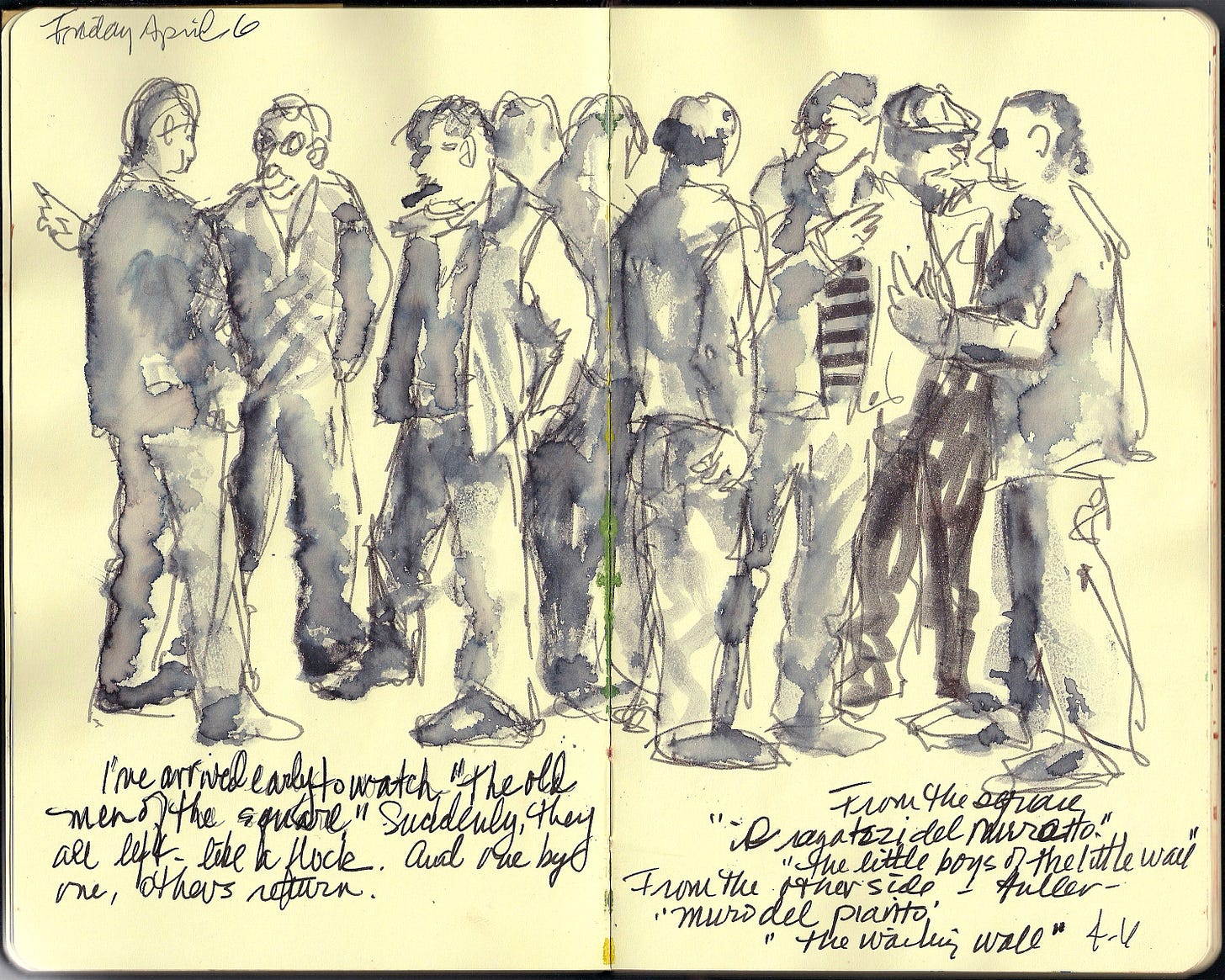

With my curiosity, sketchbook and paints in hand, I drift through a place that insists on a slower pace. Time slows down. Impressions intensify and I respond spontaneously and very much in the moment.

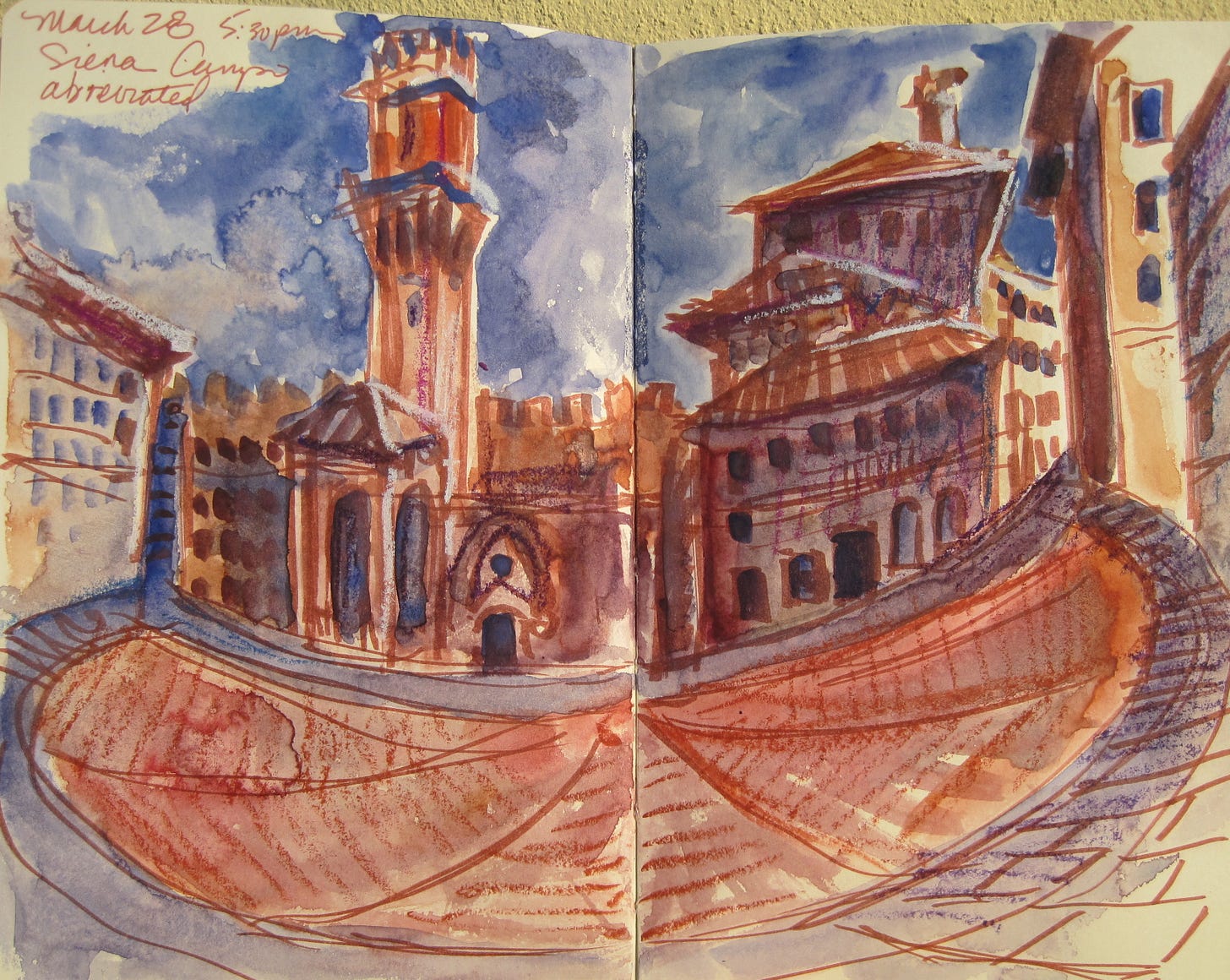

In Siena, light dominates. Each morning, the long cast shadow of the bell tower glides across the sloped floor of the Piazza del Campo like a huge sundial. In the evening, the setting sun casts its illuminating warmth, and then its shadow creeps slowly up on the bell tower. Behind the tower, the moon replaces the sun in the darkening sky. Can this possibly be captured in a painting? Or perhaps only as an impression, as Henry James suggested in the late 1800’s, “a precious presented sensibility…an infinite vision of mediaeval Italy.”

Early Etruscans flourished in Tuscany from 800 B.C. to assimilation by Rome in 1st century B.C. Fractured bits of pottery, murals and ancient tombs remain as testimony to an innovative and productive culture. From ancient paintings on museums walls, long noses and lively eyes follow me, evidence of what a Tuscan friend calls “the well-cultivated, pride of old Etruscan blood, an arrogance, an ego.”

One day a painter named Vicenzo Calli invites me to his studio. I look into his face and at the figures and landscapes in his paintings. I realize that Etruscan heritage isn’t some abstract concept predating the Roman Empire, that in this region, history isn’t something that exists in the past. Calli and his paintings represent talent and skills of a proud Etruscan heritage, a continuity of people, land and nature, or as Dickens observed in 1844, “a simultaneity of past and present.”

Monte Santa Maria di Tiberina lies at the end of a tortuously switchbacked road. One day at lunch, on a terrace overlooking terra cotta rooftops and quilted fields, the owner of the café comes out for a break. He sits on the parapet gazing over terra cotta rooftops, enjoying the same vista he’s always seen. He sees me drawing him and stays, and in the silence acknowledges my appreciation.

Some things can only be experienced by decelerating. There is an abiding tranquility, and not just between 1 and 4 when most businesses close. Family is important and friends, too: like a long table that welcomes the four-hour meal. Easter Sunday, we drive to lunch high in mountains so cold that snow was falling on distant peaks. Eight courses, proudly prepared by the mother and presented by her family, feature antipasta, soup, goose lasagna, gnocchi, beef, duck, lamb, ice cream and cakes. It ends with grappa and limoncello, somewhere near gluttony and just short of insobriety.

Wednesday is market day in Anghiari. In the well worn public squares, people greet each other enthusiastically and show off their grandchildren. From each market truck, elaborate awnings mechanically unfold. Soon a parade of all ages passes from the cheese to vegetable to meat vendors.

At coffee on early morning, I meet a man named Peter. He and his wife have raised their family here. He’s elegant and informative, and invites me and my hosts to dinner.

On sunny days, “the old men of the wall,” as Peter calls them, congregate in packs, gesturing and arguing. On rainy days, they huddle together, holding umbrellas to protect each other from the rain.

These are a people who live in a town that transcends time, who are deeply engaged in civic life. Prosperity isn’t measured materially but in connections carefully preserved.

In Florence, the immense scale of architecture and accomplishments of the Renaissance inspires awe. By contrast, the architecture of medieval Anghiari is intimate, touchable, at a human scale. While the walls of Florence are elaborately adorned, medieval towns are textured with a rich patchwork of stucco, stone and brick. The history of a building is visible in its walls, like deep lines on a very old person’s face, evidence of a life lived.

When Dickens wandered Tuscany, he described decay. But since then structures have been painstakingly protected and restored. I visit a country house that began as a watchtower a thousand years ago. The tower was destroyed in the 15th century but every owner since has contributed to its transformation into a charming country home. What remains are the stunning views of a watchtower.

In this region, architectural heritage is guarded by strict code. Open spaces within hills towns are preserved, as are borders between the town and the land. Sprawl is contained. This is a responsibility that speaks from experience and extends into the future. In panoramas, rhythmic forms and materials of the compact towns fuse with patterns in the land. The visual encounter is so intense that it can only arouse an emotional response. As Norman Carver, noted urban planner said in his book, Italian Hilltowns, “Stimulation of variety and contrast are essential to a healthy mind.”

In the Tuscan countryside, prosperity is measured by a light cast upon essential things- civic attributes established and valued over 3,000 years of connections, preservation and stewardship. They understand that our relationship with the earth must be symbiotic. We Californians, in a 164 year old state, should pay attention to the ancient Italian saying, “make haste slowly.” Or in more contemporary terms, slow down and live.