In the home I inherited, I find albums filled with fading pictures meticulously captioned with names and dates of my parents, their parents, and ancestors. One album contains things that my mother curated especially for me. There are stories about my family history, letters my mother wrote to me, and pictures of a secure and vibrant family.

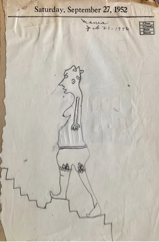

On a tattered page of early childhood drawings, only one is remarkable. We see a pencil portrait: a profile of my mother climbing stairs, brow frowning, arm and four fingers rigid. The hairstyle, rendered exactly, sweeps up from an ear. Naked except for panties decorated with frills and ribbons, breasts are pendulous and include a nipple.

As a young adult, I thought the drawing indicated talent, and more importantly, a gift for spatial problem-solving. Sixty-eight years later, I show my five-year-old’s drawing to a friend. She looks up from the page and says I’ve conveyed what a child could never have understood. “You were an exceptionally perceptive child. You’ve drawn a mother who struggles with her sexuality, not gay, with but discomfort with her roles as a female.” Though only 33 in 1953, I’ve portrayed her “as a crone past sexuality,” my friend says, “with the angular features of an unsmiling male.”

With shock, I realize this was true. My drawing contrasts with how I remember her during my childhood. Charming, vivacious, and energetic, always socially involved, busy, and stylish, she loved giving and going to parties. Now I realize I’ve drawn a woman who is stern, weighted, and depressed.

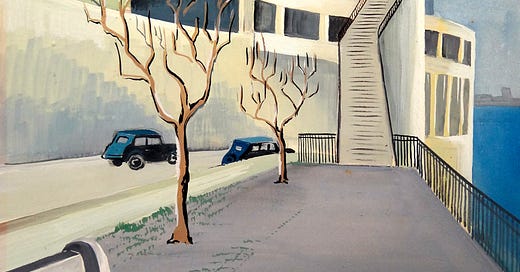

Too brilliant and talented for her time, she’d graduated in art from the University of California Berkeley in 1938 and attended Art Students League in New York during the war. She worked as an illustrator and interior designer but quit working when she overheard my father saying that she made more money than he did.

This fits with what she inappropriately shared with me when I was in high school; she’d had an affair, had fallen in love with another man. My father, loving her too, suggested that she take some time to decide what she wanted to do–leave my father or stay. She went to Europe for two months, leaving me in the care of my father.

This must have been a dark time for her. I drew this portrait six months after she returned. With my innocent artist’s eye, I’d seen beneath her party dresses.

In the home I inherited, I find two postcards from her lover. Written 14 months before her trip, he professed his love and hopes for their future. In the second, he confirms that they must stop before hurting others. Twelve years later, she ran into him and wrote a note to herself. Circumspect. Maybe.

With the lure of anything fun, my mother’s talent and ambition declined. Or did it? Perhaps she quit at that point in the creative process that everyone wants to quit. Aware that worthy work of women was seldom as validated as men, as a 1950s wife and mother, had my dissatisfied mother rebelled against restrictions and expectations of her post-war world, or just numb herself with half a valium a day?

I suspect, by the time she was very old, that she may have regretted not pursuing a more serious career. Or had she done the best she could for her generation and location?

Looking at my drawing, I remember asking her why she hadn’t sent me to art classes to supplement my mediocre school instruction. She replied, “I didn’t think you were that good.”

Really? I thought I was. How did she think we become “good?” Did she think we’re born that way?