What Lies Beneath

Beautiful, complicated, powerful, and deadly, understanding forces in a river isn’t comforting.

River obsessions

When I was a kid, I spent endless summer days along the banks of the South Fork of the American River. This was odd because my elegantly intellectual mother was hardly the camping type, and neither were her friends. Nevertheless, these ladies would pack up their silver candlesticks, tablecloths, and miscellaneous children, and off we’d go–to sleep on the ground no less.

This was a private spot called Miss Emma’s Point Pleasant Beach just upstream from Coloma where Marshall discovered gold and changed the history of California, and thus America. For a fee, it offered no-frills camping with clean restrooms and a snack bar. It offered a magnificent old cottonwood with a rope swing. How we escaped serious injury, I don’t know, because if you didn’t let go in time, you’d crash into the tree, an early lesson: risk can have consequences.

Today, this area has white-water rafting operations, an indication of how fast and dangerous the current is as it descends into the Valley. As a mother myself, I don’t know how our mothers let us swim to rocks in the middle of the river. What I remember is getting up my nerve to start far enough upstream so as not miss the rocks.

I still have a fondness for Sacramento Valley’s iconic cottonwood, its shapely leaves rustling in a breeze. It’s this particular river that I want to understand, and not just from the banks.

“In the wondrous river that defines Sacramento, a dichotomy between the beauty of the surface and hidden forces below only becomes evident from the middle of the river, not the shore.”

A novice on the wrong side of the river

I must get to the opposite shore. I hear my dad telling me that he almost drowned as a kid, trying to do just this. In a cumbersome kayak, I’m forced to leave my safe place against the shore and enter what feels like a raging flood.

It’s not a flood. As far as flows, it’s 1.5 on a scale of 5. Alarmed by the tremendous power of current through the bottom of my boat, I’m pushed sideways and downstream. I’m paddling as hard as I can and I’m not going anywhere but away from where I need to be.

Feeling a helpless failure, I’m going to be carried away. All I have is determination. With feet to spare I make it to the other side just where the river drops dangerously away.

Back safely on the other side, I ask expert friend Tom to explain to me what I should have done to get across safely. Drawing with a stick in the sandy shore, he explains how a kayak needs to be at an angle to the flow, not to the shore. Trying to hide my confusion and suppress my fear, I’m slightly traumatized and feeling a little foolish.

Returning to safety

I’ve asked Chuck Watson, a fellow who’s been paddling this river for 50 years, to explain the terminology and physics of this river: What is a haystack, a funnel, an eddy, and how do I learn to read the surface to keep me safe?

He describes how easy it is to flip at the eddyline. I ask, “What’s an eddyline?” And now I’m really scared. These are notes from a transcribed recording on January 22, 2022.

Chuck is one of those fellows who doesn’t suffer fools. This makes me nervous as my ignorance about rivers is great, but at least lesser than my desire to learn. He looks like he’s stepped out of the 18th century, fresh off some upstream dig, face weathered, hair and beard untamed.

About the Upper American River Watershed. https://sacriver.org/explore-watersheds/american-river-subregion/upper-american-river-watershed/

Chuck consults with various watershed agencies and has access to GIS maps. He’s been taking advantage of extremely low flows to explore and document features of the river that are rarely accessible. I’m interested in creating artistic and informative maps of each of the regions of the river. Over geological time, and since the arrival of Europeans, the natural area of influence and gradients of this river has changed, along with the velocity and so many other factors. Chuck understands these factors.

Hydraulics. The dominant features of a river are constrained geology, the accumulation of sediment, and how a river responds to narrowing river banks.

Riffles and eddies. From a hydraulic perspective, an eddy functions like standing water, the same as the bank. With respect to the flow, banks constrain, pressing laterally. Restricted flow gets faster. An eddy flows upstream in circles, a function of friction and resistance that creates an hydraulic void on the sides. A high velocity eddy might flow upstream at the banks at 7 mph, and circling, slow to 1 mph creating a crisp edge. A boat must keep in the center, away from the eddy edge where you can flip. When flow is 1500 cfs, for example, water is stationery and flows in circles on sides, creating a V downstream. As the river loses waves and haystacks form.

Pillows, haystacks and boils. Riffles, gradient and material in the river bed. Boils are places where the preferential direction of the water is vertical up from the bed, occurring in the eddy.

Why Chuck likes the Lower American River (AR): So what makes the recreational value on this river in particular so wonderful for you? CW: Well, we've got a lot of dams on it so the flow is very good in the summer and it's not a flat valley floor river and it's not a mountain whitewater river. It's in between so you have a variety. For most of it, the lower six miles is flat but upstream of that it's got a fair gradient with interesting riffles. It's been altered so you're not actually looking for Thrills and Spills or you'd be on the Upper American.

Chuck so you're saying that this is a little tiny feature on the lower American but on the Grand Canyon, tell me about waves that could be four feet high cresting with Whitewater on the top right and you've done that a lot. Yeah six times

CW: with respect to the thrill I don't enjoy the thrill. What I enjoy is being able to negotiate the rapids safely: the techniques and the maneuverability, not the thrill.

CW: judgement v skill

Flipping in lava is worse than not securing boat to bank. There goes your life jacket. It’s all about judgement, skill, knowing your boat. I’d rather spend time carrying rafts miles around rapids than spend time looking for a body.

The horizon line. If you can’t see it, don’t enter without knowing what risks are. Can’t see over the discrete edge on a river? Top of a rapid, entering without knowing what the risks are? Don’t enter. Another is a rock in the channel, water depending on flow, water flat on top and plunges below. Avoid that. If you don’t see waves downstream, then the depth of water over isn’t deep enough. Don’t enter a rapid you can’t see.

My conclusion

Thanks to Tom and Chuck I have a greater understanding of the complexity of a river, even as gentle a river as the Lower American (most of the time). I’ve had a lesson on the water and a second out of the water. It’s a beginning. I’ve learned that the undertoad is not imaginary, that it lurks beneath the surface, between the current and an eddy, and over the horizon. I’ve learned about the difference between judgement and skill, and that I might be kayaking on lakes for quite awhile.

A Special Place Revisited

Returning to walk the shore near William Pond, is a deeply emotional experience. In 1984, I’d found a hidden path from the pond to a channel of the river and a small sandy beach littered with fresh-water clam shells and solitude. This became my secret sanctuary from a life full of gratifying obligations and deadlines. Now the path is wide. Easier to see rattle snakes.

A path to the right took me to a peninsula that almost reached to the other shore. For many years a single tree struggled to survive at the tip. Each winter, the peninsula retreated. Now channel is wide. Storms swept the tree away and likewise, my marriage and my house on the bluff.

Sound of water over rocky river bottom

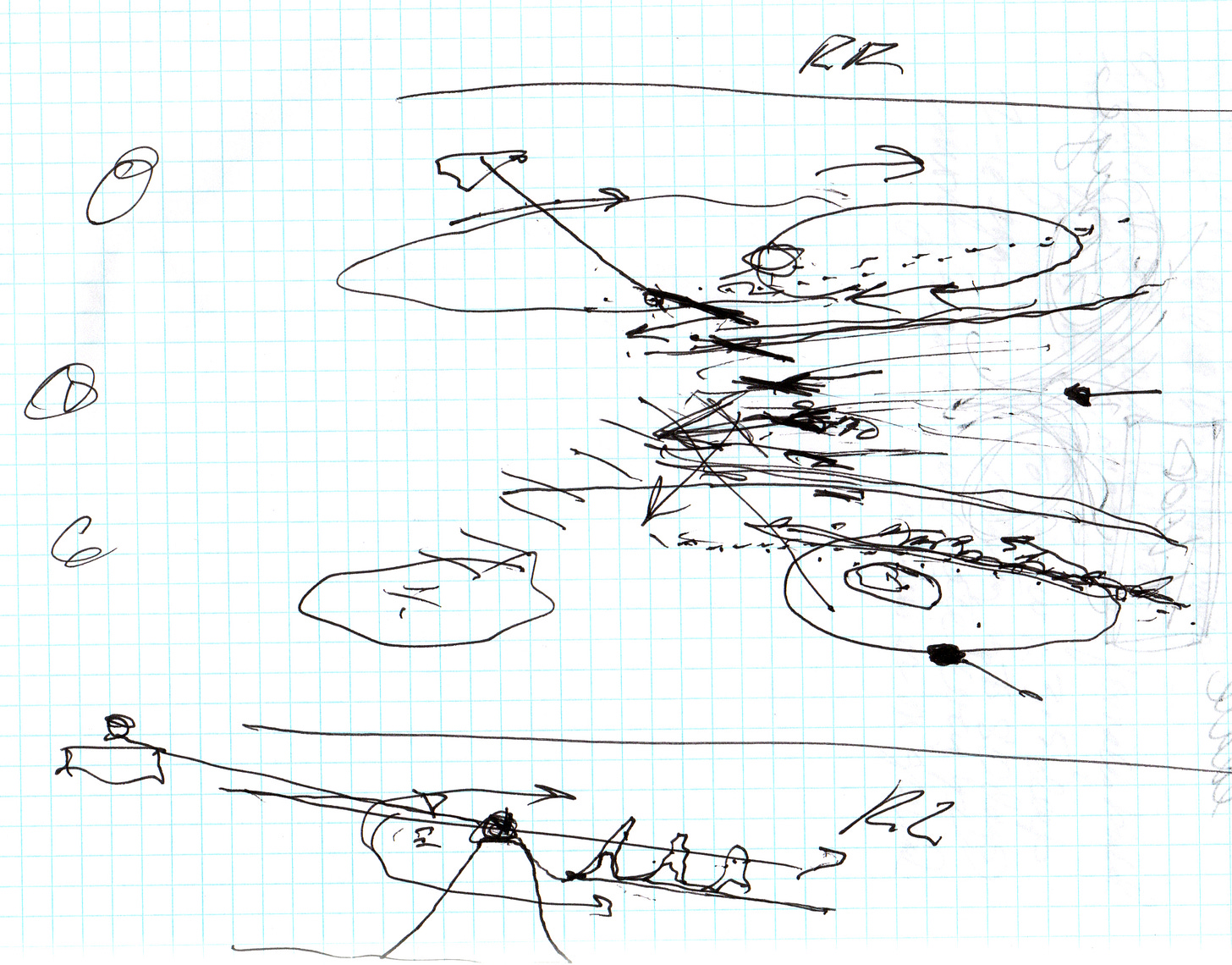

I sit awhile, watching the river flow around islands in patterns of riffles and eddys. Low water creates a soothing sound and makes these patterns easier to see. I make a drawing like I’ve made so many times before. Since then, I’ve learned that the clam shells are brought by otters. Since then, droughts have accelerated, stressing spring and fall runs of Chinook salmon who used to be so plentiful. Now without fisheries, they’d likely become extinct.

Sound of water over rocky river bottom

My walk today reveals a vast depression in a trail once filled with round river rocks. It took at least thirty-seven years, but the river finally broke through to the pond. I’m guessing at least twelve vertical feet have been washed away. At the bottom of the depression, a trickle of stream leaks from the river into the pond. Rangers have made a rock bridge across. I step gingerly.

Sounds of water recede, replaced by the smell of dry grass. Soon, the trails along the river will fill with the sweet hot smell of wild fennel, a stark contrast to winter mornings when every rock was covered in a fine layer of frost. Tiny prints like meticulous trophies marked the frost like graffiti that says “I was here.”

The trail around the pond disappears into thick underbrush. I look across the pond to see on outlet to the river that seldom existed before, and certainly not with levels this low. A bullfrog protests, a mated pair of wood ducks cruises. I saw this outlet from the river and aspire to drag my kayak up the rocky stream. All those years of looking longingly at this pond, yearning to on the water in a kayak, I never did and now I can.

A paddle on the pond

The next day I return up river with my kayaking friend, and like Lewis and Clark, we haul our kayaks up the uncertain footing of the little stream. This is how the explorers discovered America–I’m not envious. At the crest. it appears humans have created a dam to prevent levels in the pond from dropping too low. Heat and bacteria can quickly cause an algae bloom, sucking oxygen from the life within.

I experience a weird sense of achievement like I’ve done something important.

I haven’t, but when you wait so long for anything, it feels like something. There are several islands in the pond, a migratory stop for Canada geese. There are a few pairs here, but more stunning, an egret takes flight. In quiet broken only by an airplane, here’s a breeze.